For such a simple garment, T-shirts have always carried an unusually outsized political potency. There are a couple of reasons for this. For one, the T-shirt is a gender-neutral garment which is cheap to produce and circulate. But most crucially, the tee provides an easy-to-customise canvas for its wearers. On January 6th, 2021, insurrections spotlit the emergent clothing economy, geared towards all sorts of fringe political groups that might typically try to remain undetectable or anonymous. In an abundance of footage and images documenting the event, individual subjects and their clothing were shockingly easy to pick out, scrutinise, and analyse.

Image 1: Jacob Chansley photographed by Blink O'fanaye via Flickr

There was the ridiculous Jacob Chansley (more commonly known as the “QAnon shaman”), who donned the eye-catching but confusing symbolism of the horned fur hat, which he claimed was Nordic but is, in fact, native American. There was the militarised; participants wearing intimidating body armour and openly carrying firearms were more difficult to make light of. And finally, there was the sloganned with their printed t-shirts, hoodies and embroidered baseball and trucker caps. The motifs emblazoned on these garments are not always explicitly violent. Many showcased cringe-inducing agglomerations of the usual eagle-heavy patriot kitsch alongside declarative statements about freedom. Indeed, the zaniness and hyperbole of QAnon’s belief systems and its associated imagery likely delayed it being taken more seriously as an extremist group (Maheshwari and Lorenz, 2021).

For many, the armed presence on January 6th meant sentiments that had long been bubbling away could no longer be ignored or dismissed as fringe mania. This ‘fashion of fear’ (Sutton, 2023) which includes body armor, bulletproof panelling and military flourishes, sat alongside the fashion of everyday Americans. The slogan t-shirt is a mass-culture product that is emblematic of the ordinary citizen; so, whilst some of the fashion of the insurrection was spectacular or intimidating, most of it was strangely banal. I would argue that this juxtaposition requires a reconsideration of the t-shirt as a particularly salient political unit. I also believe that innovations in digital business models have scaffolded this phenomenon by enabling new forms of designing, selling and circulation.

Every political movement worth its messaging knows to embrace fashion as an essential aspect of creating a cohesive identity and communicating an ideology. Because fashion is inherently visual, political statements on the clothed body can proliferate visuals rapidly throughout news and social media in ways the spoken word sometimes does not. Katherine Hamnett’s t-shirts in the 1980s used oversized, shapeless designs and aggressive black block lettering to demand “STOP ACID RAIN” or state, as she was photographed in front of Mrs Thatcher herself, that a majority of the British public was not in favour of nuclear armament. Hamnett describes her design choices as being directly influenced by the upcoming photo-op; she knew the wording had to be legible and clear for the shots that would find themselves in the newspapers the next day.

I owned a NO MORE PAGE THREE t-shirt while I was at university, which consciously mimicked Hamnett’s lettering to suggest that pornography and world news may not – and ought not – sit naturally alongside one another. From the mid-2010s, the advent of hyper customisation online and the rise of drop-shipping business models have allowed the political t-shirt (and other low-cost products) to take on both mainstream and marginal forms. As Katie Way (2021) puts it for VICE, in the age of the political meme, this type of motto-heavy merchandise “distils a certain strain of political affinity down to its most potent yet marketable essence.”

Image 2: The absurdity of individualisation is most evident when search results for broad terms such as ‘political t-shirt' juxtapose pro-MAGA, RBG homages, anarchist symbolism, inspirational quotes about democracy, are all lined up alongside one another in stock image mock-ups.

Websites such as Contrado or Redbubble allow anyone to craft, upload, and format designs for products, which can then be purchased as individual units for low prices. Some entrepreneurs have used this technology to create entire shopfronts of hypothetical products. These are advertised using digital mockups and are only ever produced if someone actually orders them. This model has obvious benefits for those testing emerging, niche or controversial markets, as no up-front capital must be invested in the items before they can be floated to potential buyers. Commercial viability doesn’t have to be a part of the conversation anymore. And it turns out that groups like QAnon, which straddle socioeconomic levels, have considerable buying power. Not only that, but mainstream disavowal of these groups means that bigger corporations do not cater to them, and this vacuum creates a space ripe for exploitation.

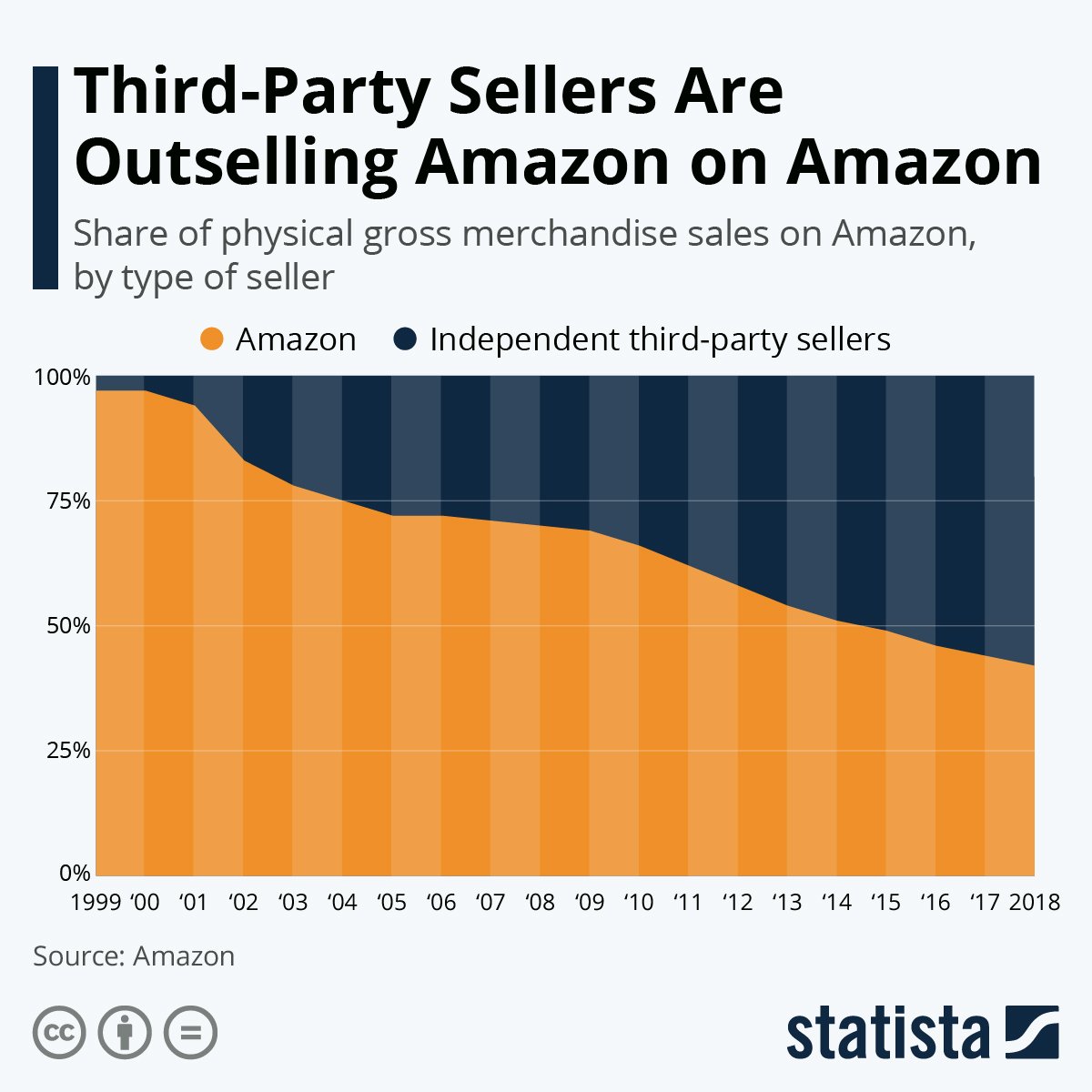

Image 2: Chart showing the growing proportion of independent 3rd party sellers operating on the Amazon platform, over which Amazon has less regulatory control.

Amazon was called out repeatedly for an apparent failure to remove offensive merchandise from its shop front (NBC News, 2018). Here again, innovations in the business model itself may be to blame for creating loopholes in the censorship process. Over half of Amazon’s sales (60%) are now produced and fulfilled by third-party sellers (Amazon, 2023). This means that they are not designed, manufactured and shipped by Amazon but by a fragmented ecosystem of makers and sellers. Unsurprisingly, this pivot away from a centralised system makes products more difficult to regulate at scale. This issue was highlighted recently by journalist Oobah Butler’s grotesque stunt selling their Delivery driver’s urine as an energy drink with little-to-no obstacles on the Amazon website.

Etsy, a leading sales platform based in the US, banned QAnon-related merchandise from its shops back in October 2020. It did this in line with its previously defined terms of sales, deeming that these items ‘promote[d] hate, incite[d] violence, or promote[d] or endorse[d] harmful misinformation’ (Farokhmanesh, 2020). Unfortunately, this has done little to stem the burgeoning economy of clothing, literature and even (somewhat paradoxically) protective face masks branded with QAnon motifs. Due to the cryptographic nature of the movement itself, much QAnon imagery is esoteric and scattered, making associated merchandise harder to spot in the street. Algorithmically, explicit metadata keyword giveaways are avoided and supplanted for vague terms like ‘tyranny’ and ‘patriot’. WWG1WGA: A string of letters and numbers becomes a mark of ownership that reads more like a number plate for the uninitiated. More arcane allusions to the conspiratorial replace skulls or traditionally recognisable white supremacist symbols. Because of this pressure to mystify QAnon messaging to evade digital detection, this type of merchandise is now able to creep back onto mainstream platforms, just one order removed from its original lexicon.

Image 3: A pro-gun ownership (and anti-federal-government interference) design from an Etsy shop.

A quick search on Etsy showed Q-themed caps, products celebrating 1776 as a nostalgic “throwback” and a T-shirt calling conspiracy theorists ‘people who figured out the truth before anyone else’ among many others. This last design was overlaid onto an image from a 1950s cookery commercial, echoing the sort of nostalgic all-American imagery of the ‘trad-wife’ movement, which has significant overlaps with the manosphere and incel subcultures. These platforms do not want to be seen to willingly accept designs that espouse hate symbols and controversial speech on their sales channels, but they are equally unable to ringfence what creators can do consistently.

Image 4: A T-Shirt design from Etsy Shop “PatriotApparel805”

While most people wouldn’t contest that clothing is a site of political meaning today, further questions should be asked in the face of responsive product design and sales platforms with a looser grip on their merchants' activities. How can the digital democratisation of product design be accompanied by safeguards to detect and intercept content promoting violent ideologies? And if we censor clothing aligned with specific causes from online marketplaces, are we solving a problem or merely displacing it? When is such a ‘dress code’ imposition appropriate, particularly within liberal democratic settings? And perhaps most abstractly but importantly, is a T-shirt ever just a T-shirt?

References:

Farokhmanesh, M. (2020). Etsy is banning QAnon merch. [online] The Verge. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2020/10/7/21505911/etsy-qanon-merch-ban.

Foresta, M. (2020). The Economy of Hate: How Online Retailers Profit Off of Right-Wing Extremists. [online] Progressive.org. Available at: https://progressive.org/latest/the-economy-of-hate-how-online-retailers-profit-foresta-201203/ [Accessed 28 Mar. 2024].

Maheshwari, S. and Lorenz, T. (2021). Why T-Shirts Promoting the Capitol Riot Are Still Available Online. The New York Times. [online] 19 Jan. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/19/business/qanon-maga-merchandise-amazon-etsy-shopify.html.

NBC News (2021). There’s Plenty of Q-Anon Merchandise for Sale on Amazon. [online] NBC News. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/fringe-conspiracy-theory-qanon-there-s-plenty-merch-sale-amazon-n892561..

PatriotApparel805 (n.d.). PatriotApparel805 - Etsy UK. [online] Etsy. Available at: https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/PatriotApparel805?ref=l2-about-shopname [Accessed 29 Jan. 2024].

Redbubble (n.d.). Political T-Shirts for Sale. [online] Redbubble. Available at: https://www.redbubble.com/shop/?query=political%20t-shirt&ref=search_box [Accessed 29 Jan. 2024].

Richter, F. (2020). Infographic: Third-Party Sellers Are Outselling Amazon on Amazon. [online] Statista Infographics. Available at: https://www.statista.com/chart/18751/physical-gross-merchandise-sales-on-amazon-by-type-of-seller/.

StefanysApparel (n.d.). I Am 1776% Sure No One Will Be Taking My Guns, 1776 Tshirt, USA Flag Gun Shirt, 2nd Amendment Shirt, Patriotic USA Gun Rights, Pro Gun Shirt - Etsy UK. [online] www.etsy.com. Available at: https://www.etsy.com/uk/listing/1110823118/i-am-1776-sure-no-one-will-be-taking-my?ga_order=most_relevant&ga_search_type=all&ga_view_type=gallery&ga_search_query=1776&ref=sr_gallery-1-39&pro=1&sts=1&organic_search_click=1 [Accessed 29 Jan. 2024].

Sutton, B. (2023). Bulletproof Fashion. Taylor & Francis.

Tamsin Blanchard (2017). Did You Know Sweatshops Exist In The UK? [online] British Vogue. Available at: https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/sweatshops-exist-in-the-uk-leicester.

Way, K. (2021). Etsy Is Full of QAnon and Insurrection Merch. [online] Vice. Available at: https://www.vice.com/en/article/93wznd/etsy-is-full-of-qanon-and-insurrection-merch.