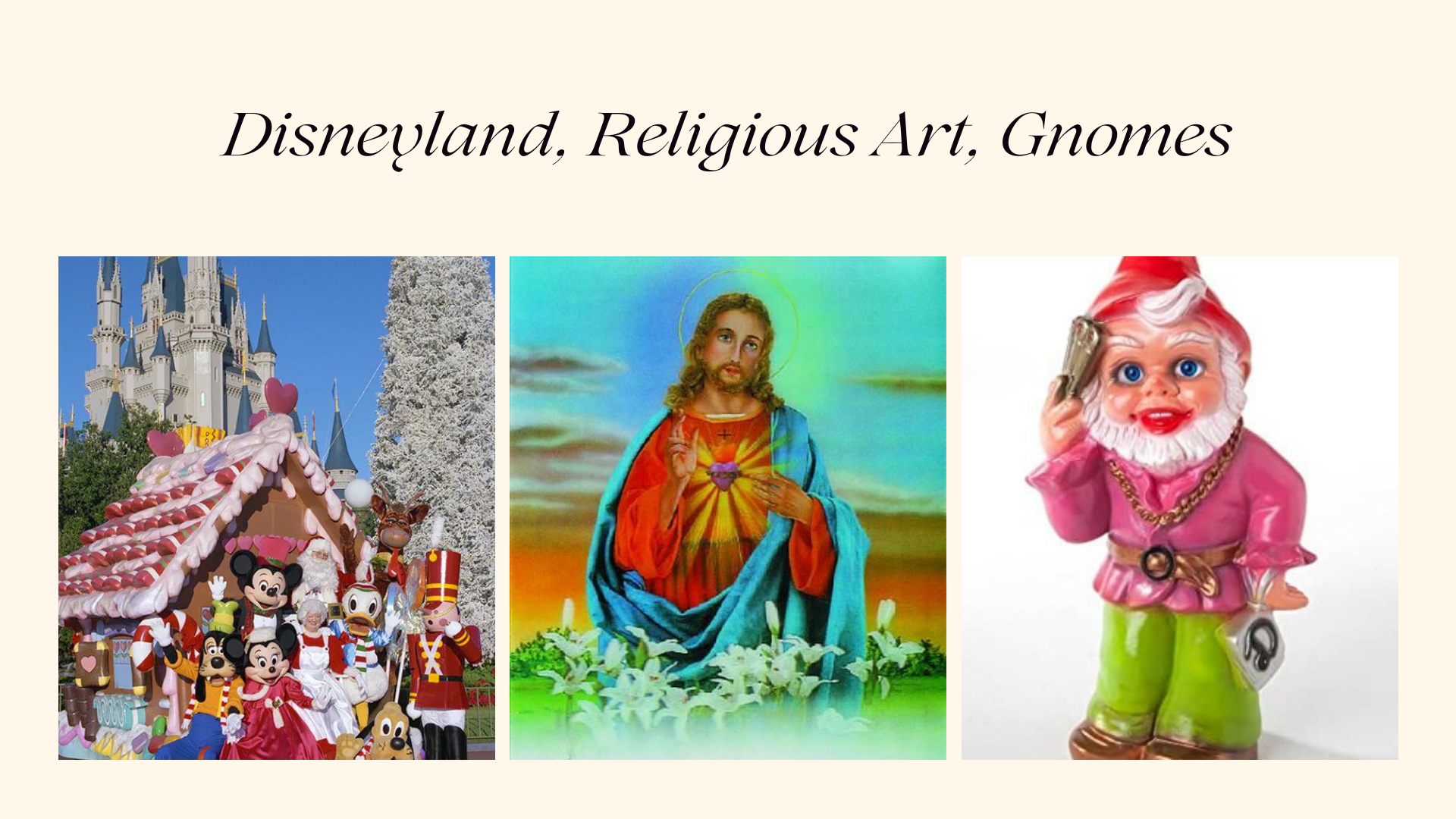

What do you think of when you hear the word 'kitsch'?

There’s probably at least one image from the montage below that springs to mind.

Kitsch aims at being universal. It tries to aestheticise (or beautify) the ordinary - but often so much so that the original motif becomes a caricature of itself. Everything is exaggerated. A little too shiny. A bit too frilly.

Disney's characters have a bit too much of a spring in their step, Jesus emits an almost alien-like airbrushed glow, and the garden gnomes’ cheeks look almost maniacally flushed. You get the idea. Something is always a little ‘off’ with kitsch, which forms part of its ironic appeal.

The etymology of the word 'kitsch' is an interesting one. It if commonly thought to derive from the German word 'kitschen' meaning ‘den Strassenschlamm Ausammenscharren’ (to collect rubbish from the street). The German verb verkitschen (to cheapen), is another likely source. The Oxford English Dictionary defines kitsch objects as "characterized by worthless pretentiousness.” While the exact origins of the term remain unknown, it first gained traction in usage by art dealers to describe "cheap artistic stuff" in the 1860s and 70s.

Kitsch takes the ordinary and the elements of mass culture that we are so immersed in that they barely register on our radar anymore, and attempts to re-use these motifs in order to satisfy what some have called 'mass fantasies' and 'mass wish fulfilment'.

This is beautifully demonstrated in the dreamy, often explicitly erotic photography of Parisian duo Pierre Et Gilles who mimic religious iconography in their outlandish celebrity portraiture. Kitsch aesthetics as a whole attempt to seduce us by appealing to our love of glamour, an appreciation for beauty, nature and harmonious compositions. Surfaces in these portraits are either airbrushed of all imperfections and smoothed over or encrusted with tactile detailing like flowers, beads, shells, or other generic glitz.

What is perceived (or relegated) as 'kitsch' is not a cultural constant. Motifs that were at the time seen as sincere, practical or even tasteful can re-emerge and take on a new dimension of kitsch contemporaneously.

One example of this is food visuals from the mid-20th century. At the time, colour photography and illustration were primarily used for commercial imagery - anything considered to be 'high art' by the establishment was still created in the moody and evocative monochromatic form of blacks, whites and greys. These works of art played with light and shadow for impact rather than a colour palette. But food is a big business, and therefore the use of colour visuals represented a new world of (sometimes downright scary) gastronomic possibilities. Proprietary food brands like JELLO, soylent green, and Velveeta (an egg yolk yellow cheese substitute) transformed produce into products.

This is the imagery of a new superabundance that emerged in the wake of World War Two. It is a blatant celebration of western agricultural triumph, or perhaps simply of greed, indulgence and decadence. The colours of the food displayed are matched in vibrancy by the table settings and interiors surrounding them. More was always more in this context. The visuals that showed off these culinary advances embraced new more vibrant and cheaper-to-reproduce techniques of colour film photography and printing to their fullest extent. Food colouring also became an important tool in any kitchen cupboard, allowing home cooks to get creative with presentation - particularly where party pieces are concerned.

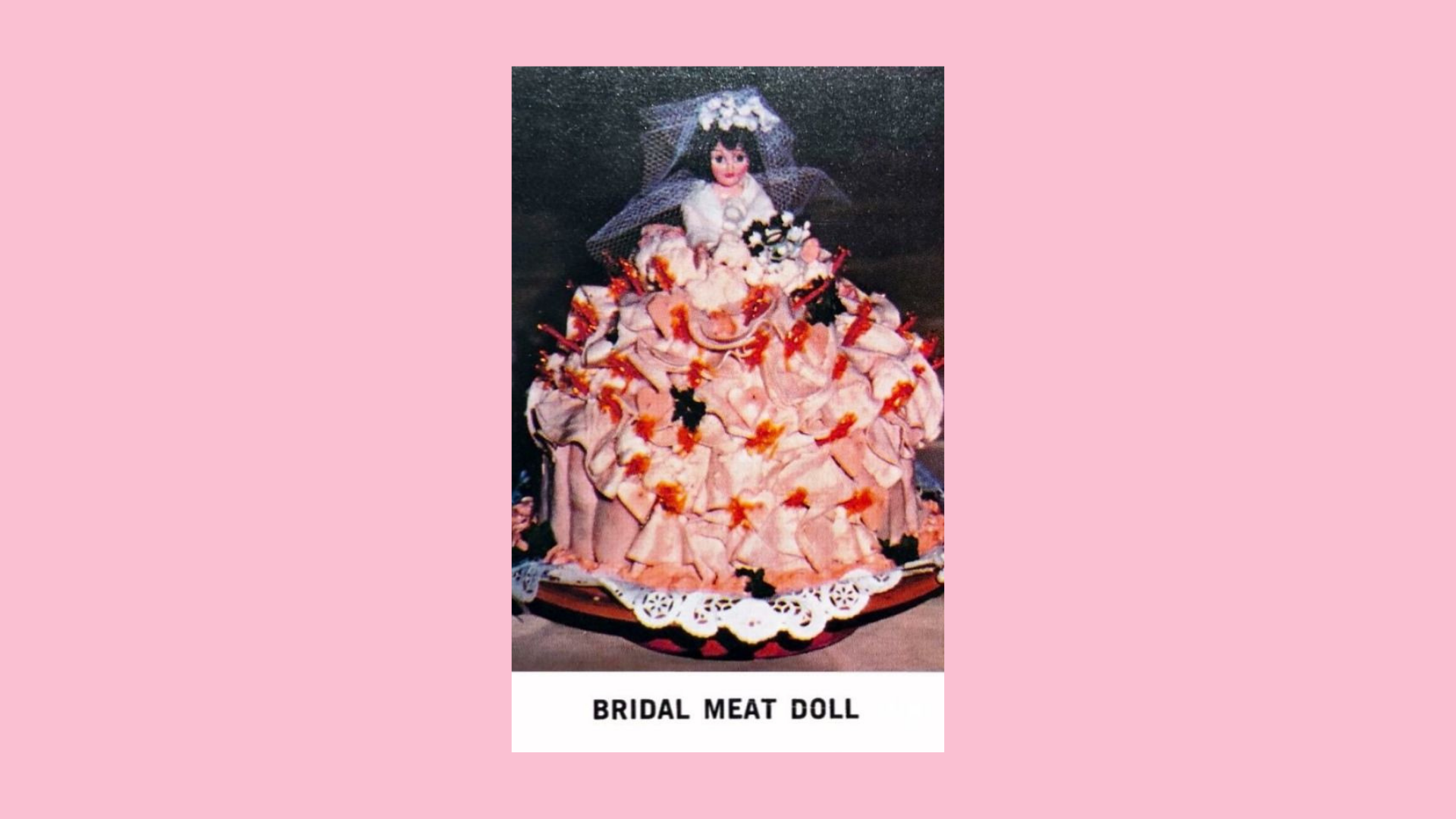

Advances in manufacturing and chemical dyes and additives for food at the industrial scale gave almost all processed foods, however previously unappetizing, a jolt of vibrant colours. Reconstituted meats go from greyish to rosy putty pinks. Desserts embrace a range of pastel shades and were frequently decorated with exaggerated feminine motifs for impact like frosted flowers or iridescent edible sugar pearls.

Food companies soon realised that in order to capitalise on the housewife market, visuals of these vibrant foodstuffs were among the most effective marketing techniques. These booklets were distributed to homes like magazines. They often included incentivizing coupons that could be redeemed in-store, swiftly converting readers into buyers and – hopefully – brand loyalists. Even sardine companies distributed official illustrated pamphlets that carefully and considerately explained the features and benefits of their products, alongside recipe inspiration and ideas for ‘plating up’ finished dishes that were at least intended to be appealing.

Most of the illustrators and photographers who would create this sort of artwork remained anonymous. Being such a colourful and rich genre, they were relegated to the commercial sphere – fine art and ‘good taste’ culture would never have accepted such saturated colour palettes and maximalist approaches at the time. There is something really pleasurably maximalist in these images - that don't limit the vibrant colours to the foodstuffs but have it spill over into the table cloth, crockery, and background balloons. We do feel as though we are entering a Willy Wonka-ish world of equally wonky desserts.

By the 1970s, food photography had surpassed food illustrations as the medium of choice. As the 80s drew near, fast food options and ‘ready meals’ began to supplant traditional recipes as the go-to option for many American households. Women entered the workplace in greater numbers and advertisers shifted their spending from print media to television, which saw higher returns per dollar. The imagery of the kitsch kitchen faded away as convenience became more important than dinner party showpieces or ‘husband-approved’ home cooking. Although where dishes like the bridal meat doll are concerned, that may be for the best for all of our collective wellbeing.

Aside from the trend for ‘Instagrammable’ desserts (mostly imported from Japan and Korea) our recent food fetishes have been much less inspiring, and a lot less kitsch. The avocado represents the dullness and fleetingness of our current culture. Avocados require chillis, paprika or generous helpings of salt to create any impact on tastebuds whatsoever. Leave one unpeeled for a day too long and it will have turned muddy brown inside. Perhaps this is a rightful revolt against processed, chemically spruced up profferings of the past: we return to nature with a dull lumpen paste on a slab of sourdough and pretend to be satisfied.

That kitsch lives on almost exclusively in desserts or highly processed branded foodstuffs only reinforces that it is a style that is made to appeal to our sense of childlike indulgence in the sweet, the fluffy, and the sprinkle-laden.

The kitsch kitchen may disgust us with some of its more experimental food pairings (and its persistent preoccupation with the rabid gelatination of almost anything) but at least it endeavoured to inspire. The imagery from this period is not only a record of the food habits of the western world at this time, but a reminder of the golden era of entertaining – when eating well and impressing guests was an integral part of what was ultimately a much less atomised suburban society. If a great criticism of kitsch is that it is purely based on surface stylisation and frivolous decoration, then employing this to delight party guests and spoil them with the care, time and ingredients taken to create these displays seem among the most worthwhile deployments of the genre…. Even if the food starts to taste sickly after a couple of bites.

A second cultural touchpoint that is evidence of the value of kitsch is the evening bag…

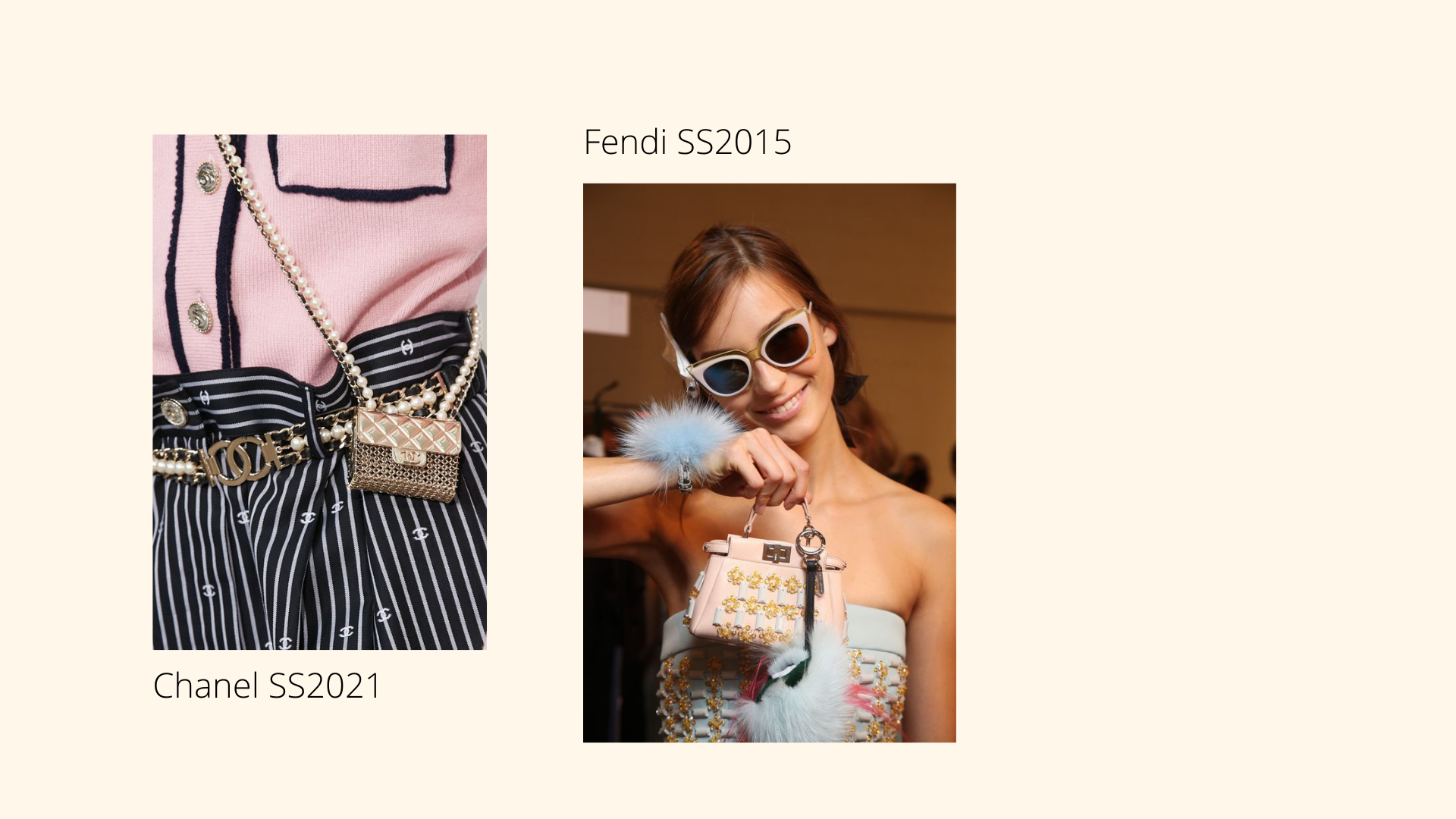

The evening bag eschews functionality for fantasy, often employing the visual tropes of bad taste to make a statement or act as an icebreaking talking point. It's emphasis on decoration over utility makes it a form of kitsch, particularly when designers make the most of this to push the limits of good taste and blurring high and low fashion forms.

Evening bags usually rely on being tightly held by at least one hand throughout the evening, so they enjoy a particularly intimate physical relationship with their owner. They are also, by design, generally extremely impractical. As such, they lend themselves to a degree of whimsy that would not be possible in, for example, the laptop bag product category.

Their smallness is almost snobbish – why would anyone need anything but this slim silken envelope after all? As American socialite, Blaine Trump once said ‘you just want evening bags to disappear and be objects of amusement.’ The bags only come out at night and therefore exist only for play. Of course, some evening bags actively embrace old-school elegance, relying on meticulously branded metal hardware to designate them as objects of status and desire. Others knowingly adopt kitsch aesthetics, forcing us to consider where novelty party props and polite society clash – leaving a potentially unpalatable fashion taste in one’s mouth.

Their smallness suggests that a woman's needs are taken care of and that she does not have to carry items for all eventualities. They are the anti-thesis of the organic cotton tote bag which has come to embody the sustainable coffee-shop-table-top working culture and are often made from illogical materials like organza (notoriously slippery), metal mesh (catches on everything) and even the superbly smashable seashell.

Dolce & Gabbana's seashell bag from the late 1990s embodies the surface pleasures of kitsch (and uses a material that crops up in other areas of the kitsch aesthetic, like ridiculous baroque-inspired shell art). The shells are not only delicate but noisy and a practical nuisance. Still, they are a talking point and invite others to swoon over your purse. And of course, the bag is lined with their signature leopard print fabrics - another pattern that confidently straddles the designations of tackiness and luxury.

There has been a collapse in the distinctions between high culture, mid culture and lowbrow culture. This has been accelerated by movements like surrealism and pop art, that made unexpected juxtapositions with familiar motifs and repurposed commercial motifs in a 'high art' context - as in these crisp and sweet packet-inspired Anya Hindmarch evening bags from the early 00s.

This disintegration of clear categories of what you could call 'good' 'bad' or 'popular' taste has been further complicated by phenomena like ironic consumption - in which consumers deliberately purchase or indulge in items or art they know to be bad taste.

There has also been the conception of a market category called 'accessible luxury', that has made designer pieces and the ownership of high-end items more normalised across social strata. The proliferation of the symbols of luxury often dilutes them - and the influence of streetwear and the omnipresence of counterfeit luxury products means that even bootleg designer items have become desirable objects.

This phenomenon is kitsch in that the deception of the bootleg item is actually celebrated and takes on a new sort of value in an ironic, fun, or tongue-in-cheek sense. That is, we see in the brazen fakery of imitation designer items a revelation of how artificially we present ourselves in the world, and choose to celebrate it rather than be ashamed of it. Gucci and Supreme have taken this double bluff approach to the next level with their recent collaboration in which you can pay true luxury prices for an item that proudly states its own (fake) fakery.

Jeff Koons and Louis Vuitton also pushed the limits of real and fake with their collaboration. If kitsch mimics reality but is, by definition, falsified, its proliferation has only accelerated with the advent of industrial mass-production. Whether copying a pre-existing work of art or assembling a pretence of reality, the straightforwardness of kitsch puts itself forward as a visual contradiction: it is a 'real forgery'

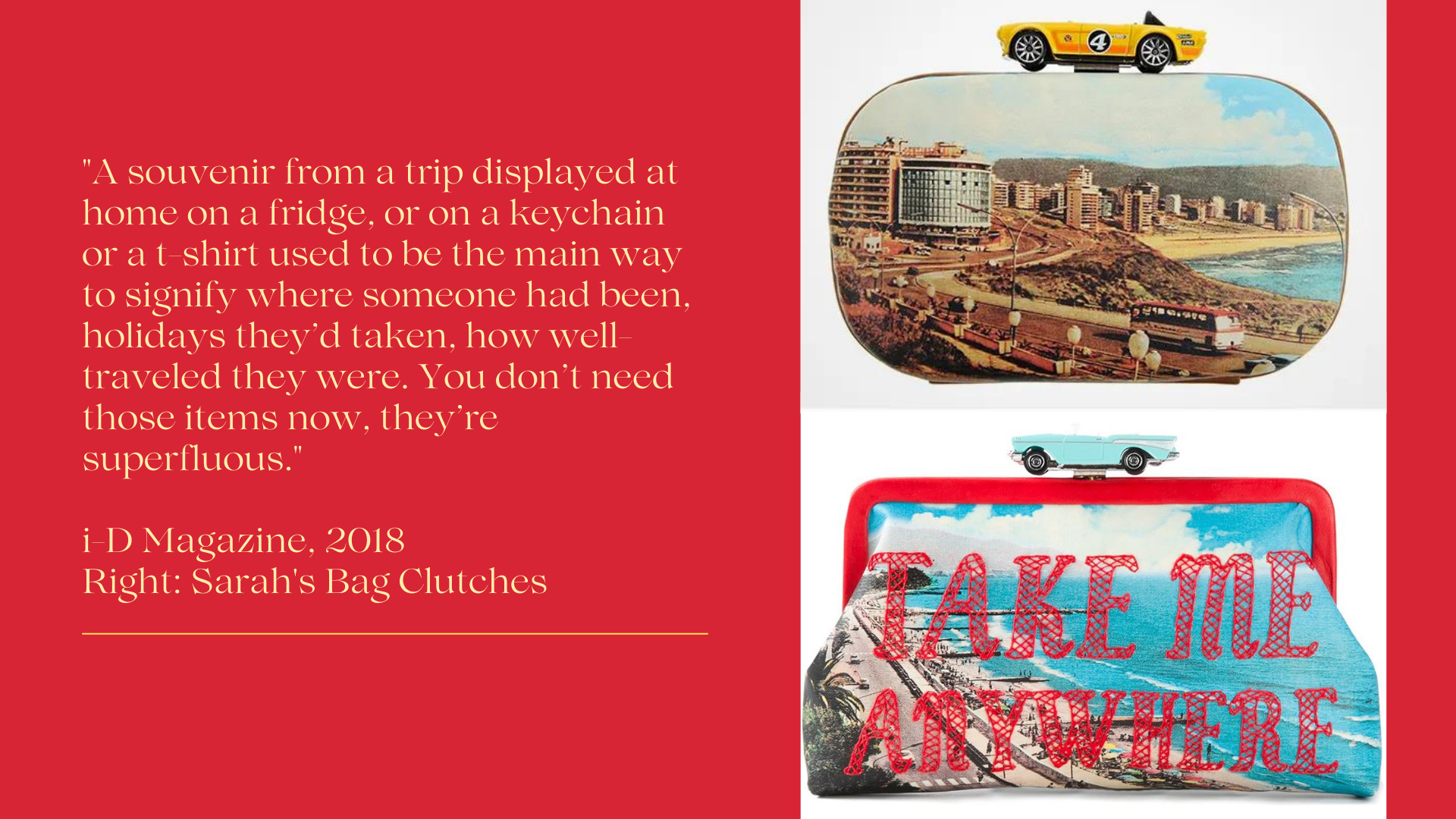

The influence of mass reproduction and homogenising consumer culture is clear in tourist kitsch - which uses the imagery and saturated colour palettes of travel photographs and advertising slogans - to make places desirable. i_D Magazine notes that this trend resurfaced as kitsch because these trinkets and objects are now almost completely obsolete. When was the last time you sent a postcard?

They have become superfluous and nostalgic, appealing to a sense of escapism and relaxation in the familiar turquoise seas and golden beaches.

The most pertinent example of the kitsch evening bag though is the Judith Lieber minaudiere. The term minaudiere was coined after the verb ‘minauder’ meaning ‘to simper or charm.’ This was the apparent modus operandi of another American socialite – Florence Gould - who inspired the first version of one in 1933. The minaudiere combines the functions of the handbag and the makeup compact in a rigid frame – allowing its owner to store little more than a credit card, lipstick and cigarettes within (although recently they have adapted to accommodate the omnipresent iPhone and unwieldy vape, too).

Each Judith Lieber bag takes between 3 and 7 days to make and they often take the form of extraordinarily mundane items. Each minaudiere is bedazzled with thousands of tiny rhinestones, coating the sculptural surface of the bag in ostentatious glitteriness. Beading and crystallised embellishment are tactile, finicky and labour-intensive which ought to accord them a sense of exclusivity. But Lieber consciously counteracts this by opting for designs that mimic everyday objects, popular culture motifs or trashy staples of American contemporary culture. The statement may not be a particularly original one – combining high craftmanship with low culture – but its vulgarity remains effective as a form of sartorial satire that only the 1% it might effectively skewer can actually afford to engage in.

Shininess still has strong ties with femininity in the west, where most men long ago renounced their interest in gilded garments for stiff selvedge denim and navy linens. The evening bag is a product that is knowingly impractical, often too delicate, and retails at a price that renders its cost per wear shockingly inefficient. In many ways it is the ultimate luxury, but it accessorising with an evening bag gives us permission to properly ‘clock out’ of work and responsibility-mode.

Can you reach me out of office? No, you can't. Because my tiny bedazzled rose the size of my palm won’t fit my phone. Or any paperwork. And that is a feeling that is increasingly hard to achieve - of pure release from responsibility. The clutch therefore takes on a new connotation of freedom.

So to conclude - is there value in kitsch?

I think there is. Kitsch is often mocked or designated as tasteless tat - and that isn't necessarily wrong. But I think there are some merits to the colourful world of kitsch,

Kitsch gives us permission to enjoy things that we have long been are not serious, high art, or in good taste. It frees us to get lost in abundant mountainscapes, rippling sunsets replete with majestic dolphin silhouettes, or even the inviting sequinned surface of an evening bag. Functionalism and utility are all well and good, but they reinforce the idea that we should always be 'on' - always multi-tasking, always on the go, and always trying to extract the most amount of value from a single object. Kitsch says slow down - and don't overthink this.

Kitsch also challenges us on what is real, what is fake, and what is really fake or faking the real.

It forces us to cast a more critical eye over all of the visuals we come into contact with and assess them - from the media we consume to the magazines we read, the clothes we wear and the art we see in museums. With screens now embedded as a permanent feature in our daily lives, deep fake technology and lazy manipulations of visuals being used to guide popular perceptions of events, 'reality' is increasingly being sold to us as negotiable. Kitsch prompts us to be more conscious of the limits of authenticity in context.

I hope I’ve persuaded you that through this short journey in kitsch being useful and frivolous are not, in fact, mutually exclusive. Kitsch offers us the comfort of nostalgia and sensory pleasures – like the plentiful plated-up feasts of the past or a gorgeous unaffordable purse. It indulges us with decadent flourishes we’ve been commonly shamed into pretending we don't derive sincere enjoyment from. And perhaps most crucially, it engages our critical faculties as we read fashion, form and flavour and are forced to consider what is ironic and what is earnest.

Seeing the world with a healthy cynicism will not only leave us more freedom to enjoy the visuals around us but allow us to accept that sometimes the aesthetics of bad taste can still convey good, and often important, ideas about society and culture.