Who Was Sonia Delaunay?

Who was Sonia Delaunay? She was an avant-garde artist, a pioneering textile-designer, a woman whose influence extended to some of the biggest names in 20th-century art (to name but a couple: Chagall and Klee).

However, Delaunay wasn’t just an artist or a woman with a vision: she was a veritable whirlwind of boundary-breaking artistic expression and design. As early as 1912, Delaunay was already dabbling in abstraction - before even Malevich, Mondrian or Miro.

Her particular theoretical approach to abstraction was not lauded in her time. It was rejected in favour of less lyrical geometricity and a more rigorous process. The ‘abstraction ‘ element was present in the artistic work at the time - but the ‘expressionism’ that implied an intuitive process was lacking. She aimed to marry the worlds of order and architecture with the fluidity and freedom of tone and form - which Jacques Damase characterised as the 'rational in the irrational.'

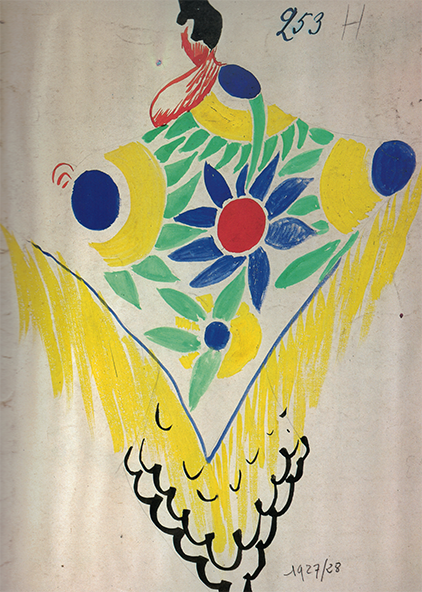

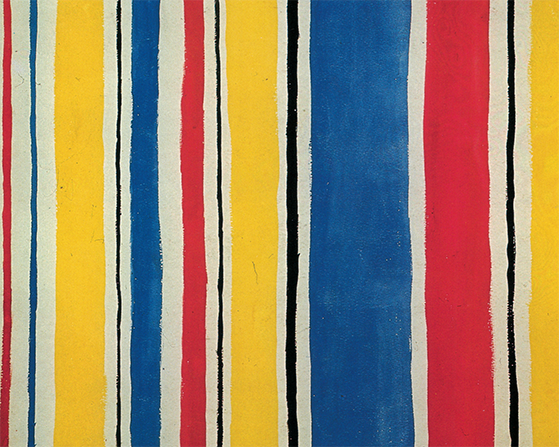

Silk fabric, ca. 1927

Relationships of Colour and Form

Delaunay's abstraction process first breaks down colour and form into 'manageable' elements. This then allows for a more dynamic exploration of the interaction of these elements with one another. She once described her childhood drawing teacher, a rigorous German woman, as leaving her 'no hope of languishing in chance and vagueness.'

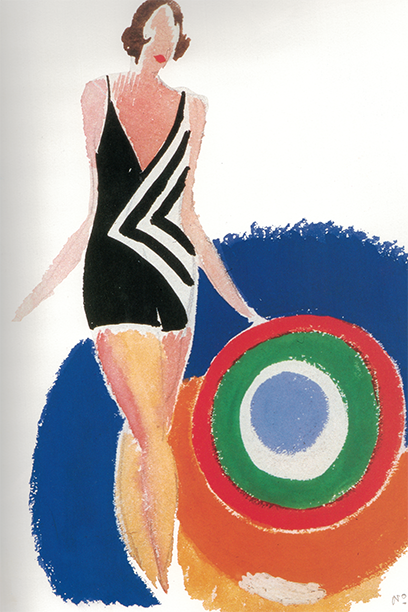

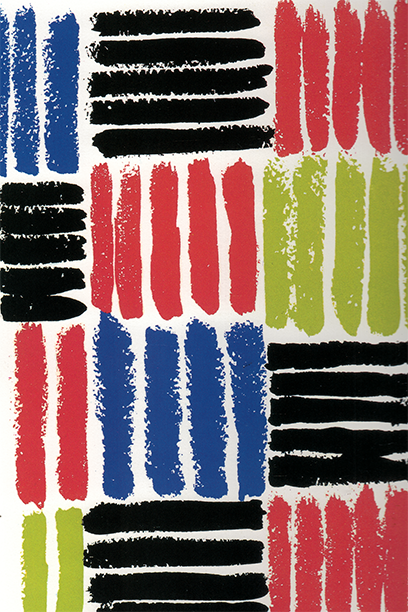

Fabric design, 1925

She describes herself as "studying the independent lives that colours acquire when we liberate them from their subject matter." Hers was a return to a pure form of artistic exploration, untroubled by preoccupations of symbols, semiotics and allegories.

Delaunay described herself as examining ‘relationships of colour’ through her work. The fauvist influence that crept in during the post-impressionist era is clear insofar as colour is liberated from its usual real-world connotations and allowed to exist freely on the canvas as an element unto itself.

Art & Fashion

In 1927, she was invited to give a talk on “The Influence of Painting on the Art of Clothes” at the Sorbonne in Paris, one of the earliest examples of an academic institution not only acknowledging this relationship but providing it credibility by offering a platform for the discussion surrounding it.

Delaunay aligned herself with Dali in that she was not afraid to allow her creative practice to bleed into the realm of the commercial. In 1920, this became a necessity as her existing income was compromised due to the Russian Revolution. Her designs ended up as posters for films and performances, fabrics, and even ready to wear garments. Her continuing preoccupation with freeing artwork from the traditional hanging canvas was the obvious motive for her fashion design. After all, is there anything more tangible, more fluid, more grounded in habitual human experience than clothing itself?

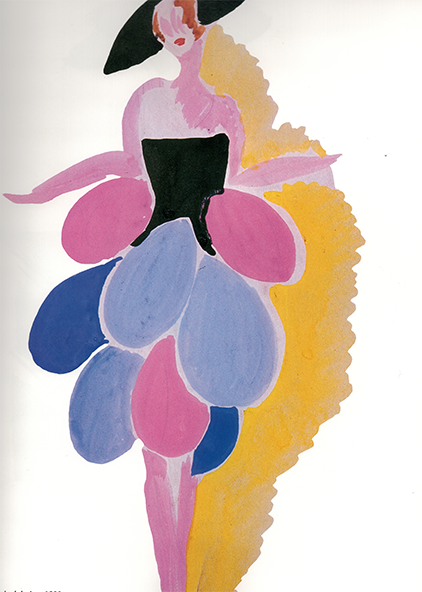

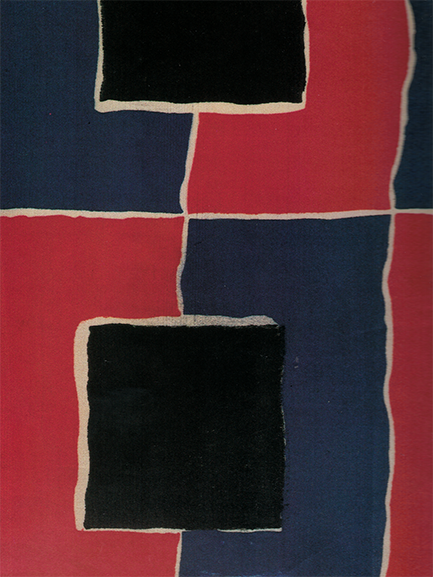

Coat, 1926

She referred to turn-of-the-century fashion as going through a ‘destructive period’ that marked the gradual obsolescence of womenswear that restricted movement and activities (such as corsets, bustles and over-the-top headgear). She then suggested that the following period in the development of womenswear must be 'constructive' - edifying through garments the vision for the role women were to take on in society.

With her textile designs, she moved away from the figurative, decorative motifs that were the norm and instead 'created' original signs and symbols removed from a worldly context.

She also felt that the fabric could not be seen as separate from the end garment itself. Traditionally, fabrics were made using popular pictorial prints and then their application was considered. The shape and cut of the piece would not be an afterthought constructed around the length of fabric: both elements were to be integral to one another. The silhouette must flawlessly accompany the print and vice versa. Her husband Robert Delaunay perfectly explained this symbiotic approach: "Sonia is simultaneous."

Portrait of Mme Mandel by Robert Delaunay (wearing one of Sonia’s ‘simul;taneous dresses’), 1923

Indeed, her first fabric designs were released with the following words printed around the edges: "Sonia Delaunay - Atelier Simultané." This clearly honoured her desire to not have her commercial work be seen separate to her primary fine art practice. This was a bold move at a time when the spheres of 'high art' and 'consumables' in any form were rarely seen to overlap or interact in any arena.

She saw fashion not only as a mirror of society but also as a vehicle for pro-actively guiding its formation and priorities.

An Enduring Understanding of Design

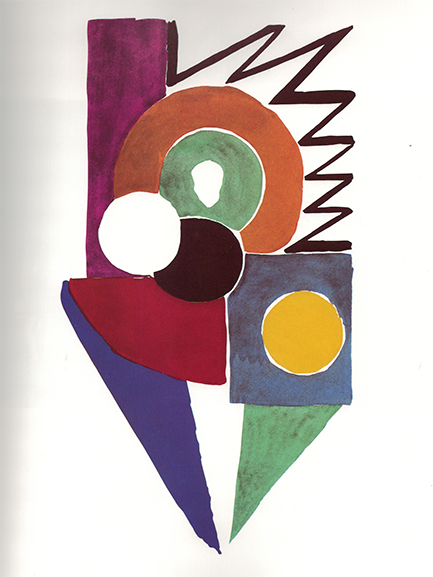

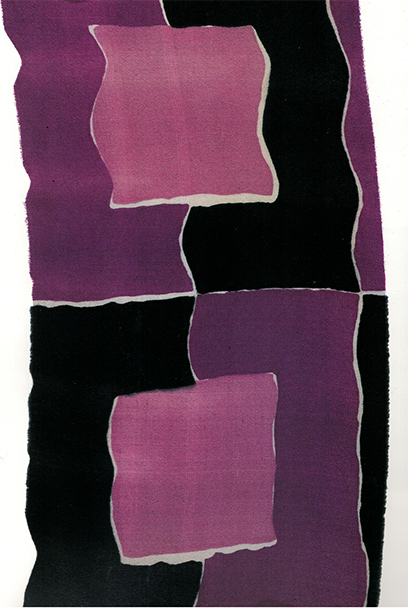

Scarf design, 1943

"Geometric designs will never go out of fashion because they have never been in fashion," Delaunay once declared. Her designs retain a lasting appeal that makes them inappropriate for those seeking to indulge in the typical aesthetic we associate with the 1920s. They give us none of the nostalgic sentiments of Great Gatsby-esque art deco designs or subversive flapper-girl glamour.

Her approach to work remained youthful - she brought energy and vigour to her practice well into her 80s - and she was a prolific creator. The patterns and colour harmonies that may seem intrinsically harmonious to viewers were, in fact, the product of countless repeated explorations and studies.

Delaunay resented artists who attempted to "shock people with eccentricities" and likened it to a distasteful circus of controversy for controversy's sake. She implied that some integrity had been lost in this art-world performance. By refusing to engage in this, and following her "innate sense of rhythm", her artistic work and her fashion have continued to maintain contemporary appeal that doesn’t lessen as decades pass.

As Art Vivant declared in 1925, Delaunay was - and still is - the queen of her own 'kingdom of abstraction.'