This one means a lot to me. I really wanted to get an article published in a journal whose main focus wasn’t fashion. In part this was as a challenge to myself to be able to frame why and how fashion is important to other fields, and in part to just expand my profile a bit as an early career researcher. Surveillance & Society has been publishing interesting and interdisciplinary work as a matter of course for many years, and I feel really privileged to now be a part of this record.

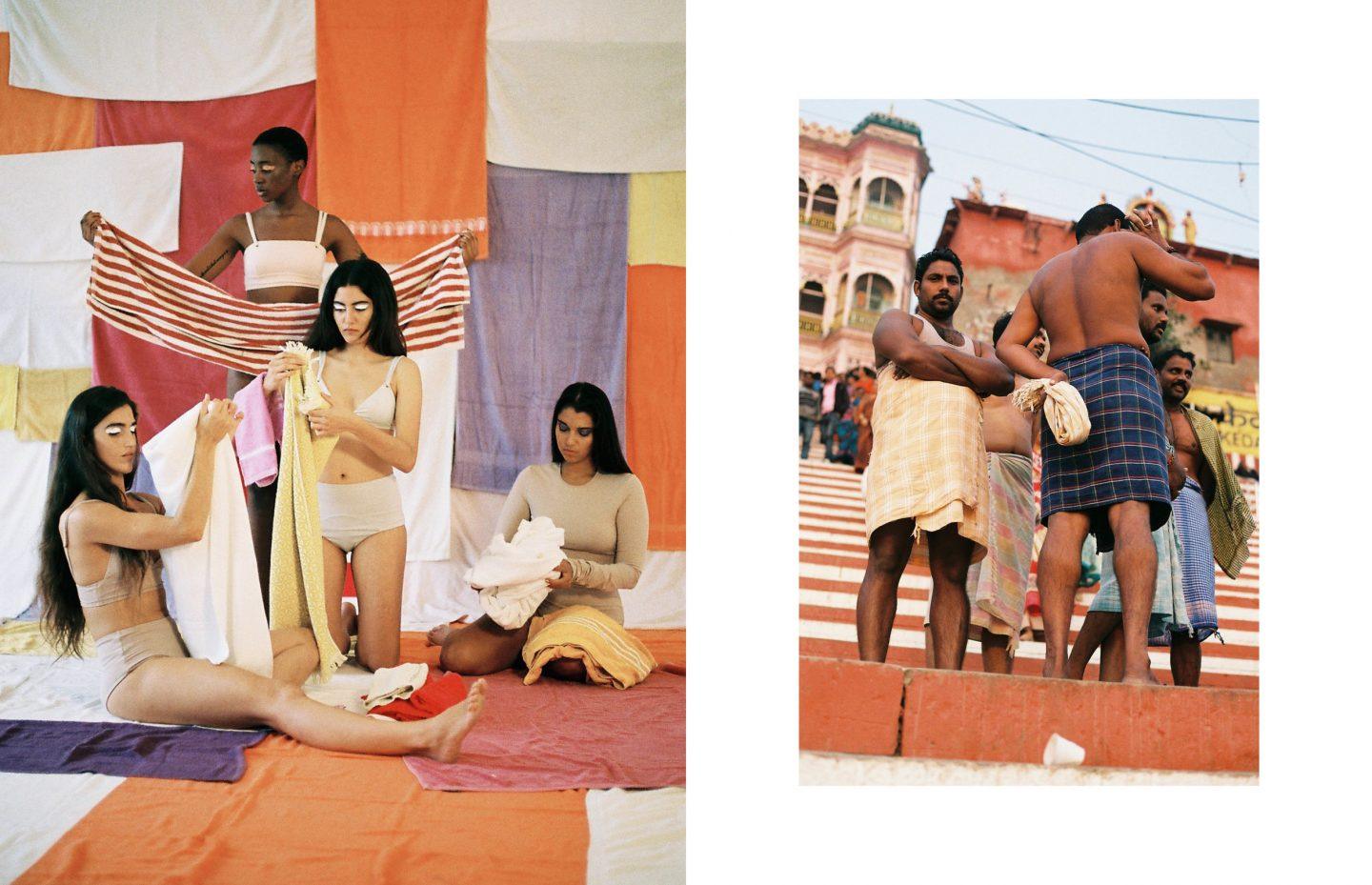

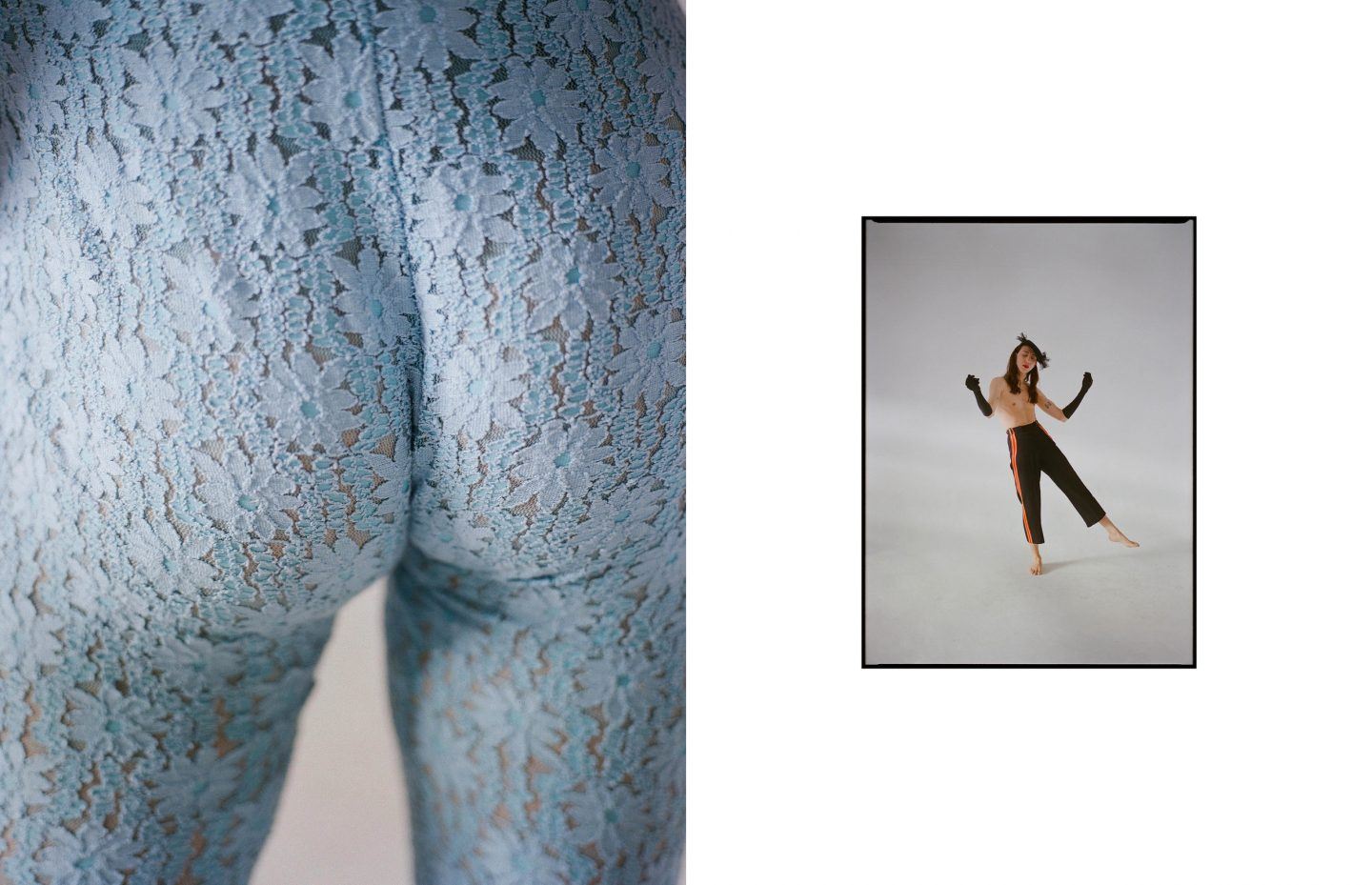

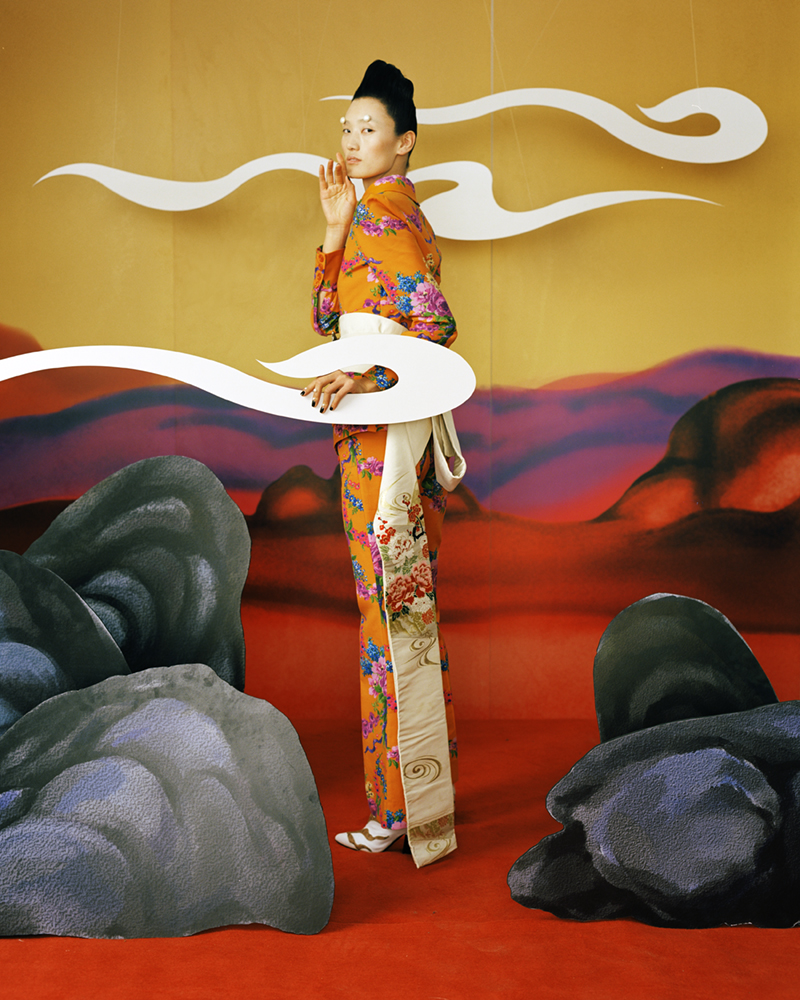

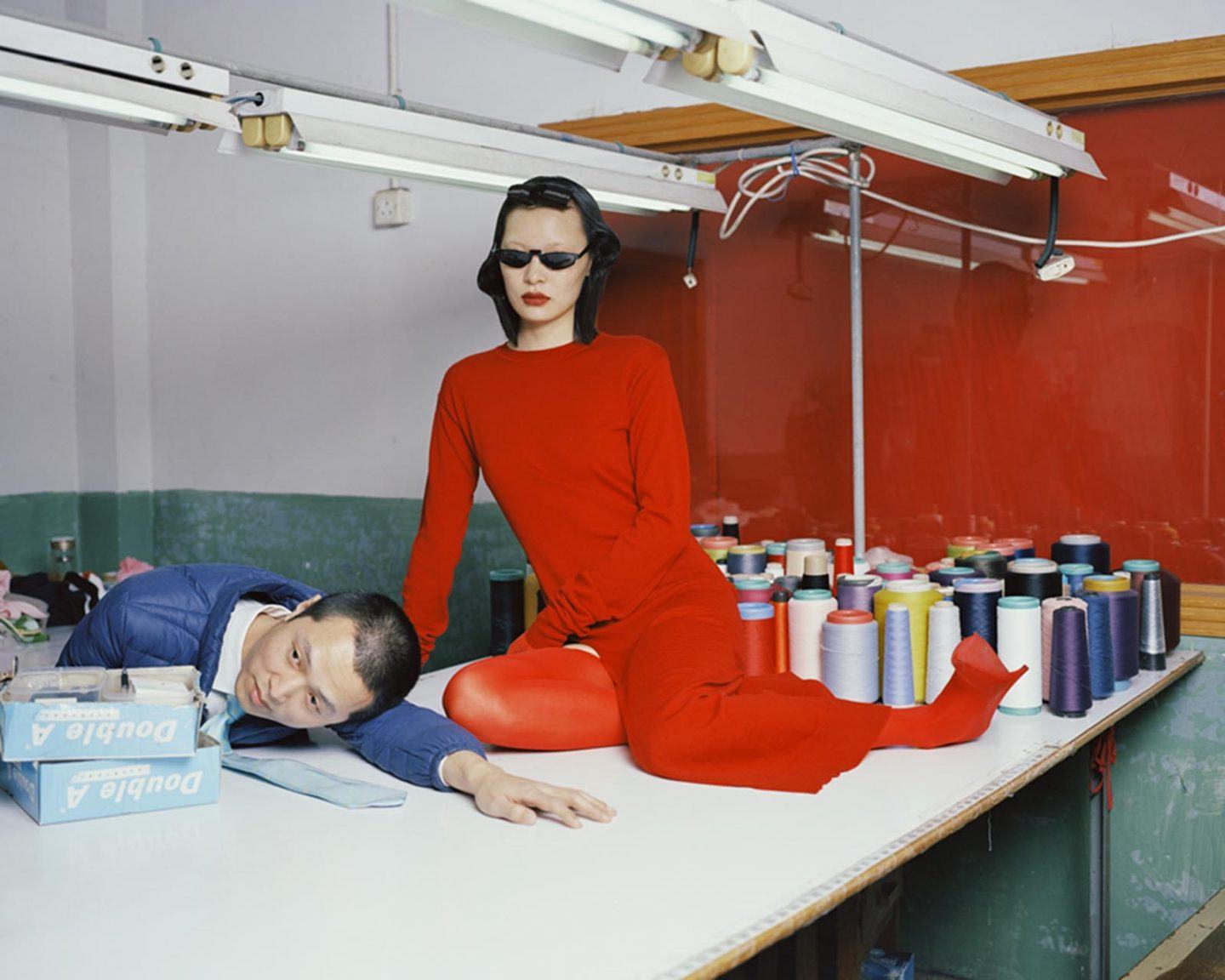

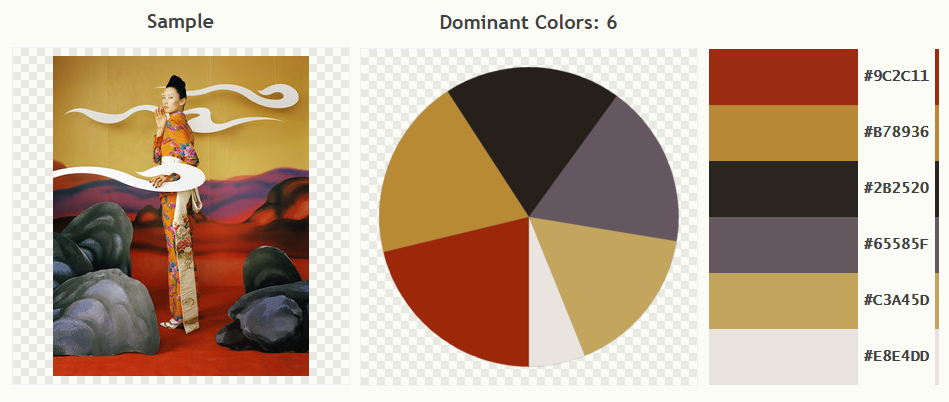

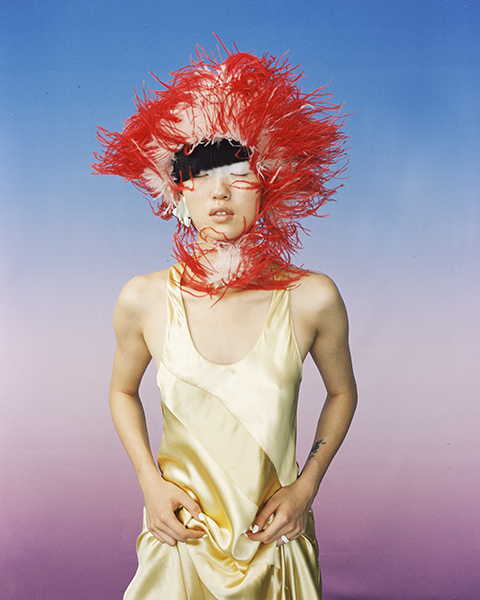

I would like to thank Atte Tanner and Alice Rosati, who were incredibly generous in granting me permission to use their images in my work. Many people are dissuaded from writing about fashion images because of the huge cost of copyright (which institutions should, but seem to rarely, subsidise). I think that helps to obscure the impact that this medium has on the culture, aspirations, anxieties and politics of the moment.

Abstract

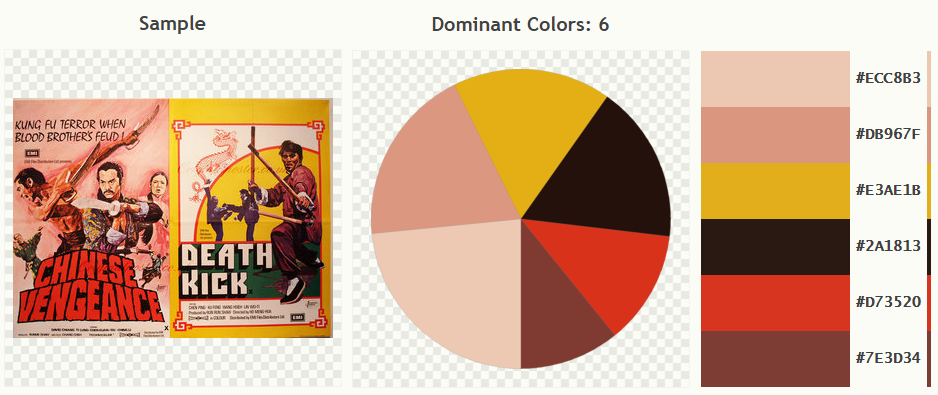

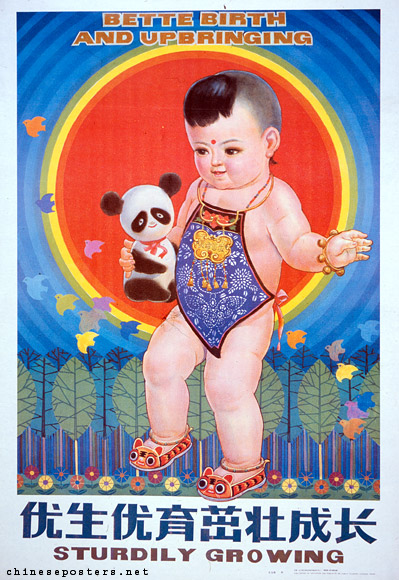

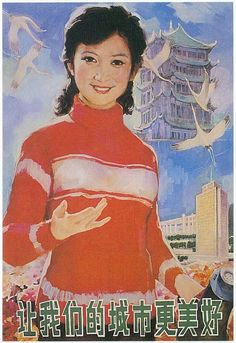

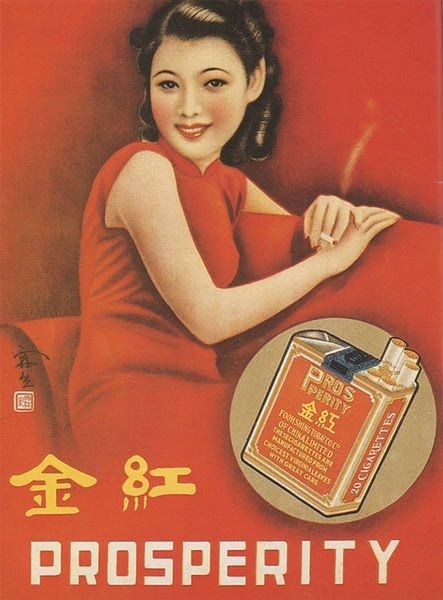

The burgeoning market for wearable technologies with surveillance capabilities is reorienting our relationship with our bodies, privacy, and digital data. This expanding sector has prompted an exploration into how the surveillance of the individual body has been normalized more broadly in the fashion sphere through its visual communications practice. To this end, a multimodal critical discourse analysis following an adapted framework examined a series of photographic editorials and identified two overarching trends that characterize the representation of surveillance in female-focused fashion consumption contexts. Firstly, by adopting a visual style that uses analog aesthetics and obsolescent technology, contemporary surveillance’s obtrusive and expansive reality is obscured and replaced with hauntological nostalgia. Secondly, by framing the act of self-surveillance via screen technologies as erotically charged and potentially empowering, the body’s surveillance is celebrated rather than scrutinized. With close reference to two specific case studies, I demonstrate how these visual treatments can be interpreted as downplaying concerns about privacy and assisting in accelerating the collapse between public and private spheres. I argue that the fashion media’s aesthetic softening of surveillance has culturally foreshadowed an expansion of surveillance capitalism manifesting in the current interest in, and demand for, fashionable wearables.

Read the full article here (it’s open access so anyone should be able to open and download it).