Something strange is happening on the streets of England. Young women who might usually wear jeans + nice tops, or velour tracksuits in juicy, bold colours are instead opting for what I can only describe as babyfied fashion. Seams disappear completely and buttons are replaced with foolproof poppers, material is so soft and synthetic that it moulds to the body and absorbs any sweat like a sponge, and the colour palette is pastel-pale or totally nude.

Initially I assumed this new aesthetic was the natural progression of Skims-mania; wherein the Kardashian endorsed shape wear brand had transcended the outer layers to become the outfit itself. Perhaps there is an element of this - fashion becomes less and less fussy but must maintain sex appeal and intrigue (in my opinion, a contradiction in terms). The obvious solution is to maintain the dullness of underwear but to expose it, lazily ticking the eroticism box without the effort of pretence or cost of craftsmanship. The fast fashion model has catalysed this phenomenon, too. Fast fashion creates products with minimal pattern pieces and detailing, so simple silhouettes in artificial fabrics are a logical choice. Grey marl can be used to create infinite garments, after all, whereas specialised prints requiring specific placements are much harder to metastasise across product categories.

Rice, N. (2022). Kim Kardashian’s SKIMS Doubles Its Valuation to $3.2 Billion: A Look Inside Her Empire. [online] PEOPLE.com. Available at: https://people.com/style/kim-kardashians-skims-brand-doubles-valuation/.

On reflection, the evolution and exposure of shape wear is just one aspect of the babyfication of womenswear. Apart from nude mimicry and the mass-production friendliness of such styles, the growing acceptability of loungewear, the infantilisation of women at large and a new wave of sensory nostalgia explain the trend. The fashion trend cycle gives permission to the public to embrace nostalgia year-after-year through the revisitation of previous eras of clothing, but also of their own lives. I have seen many late 20-somethings on TikTok ‘rediscovering’ Y2K style for the second-time recently.

It is no surprise that lounge wear has become more acceptable post-COVID. Lounge wear represents a rejection of aspirational dress which can be interpreted as comfort with ones position or a disillusionment with the economic landscape. Rather than ‘dressing for the job you want’, lounge wear says ‘where are those jobs meant to be anyway?’ And yet studies on enclothed cognition keep confirming that dressing ‘up’ seems to improve our performance, as well as other people’s perception of our performance. The lounge wear revolution rejects the real strategic impact of wearing ‘proper clothing’ in favour of personal cosiness, an understandable if somewhat self-defeating strategy for the age of AI job applications, promotion freezes and lay-offs.

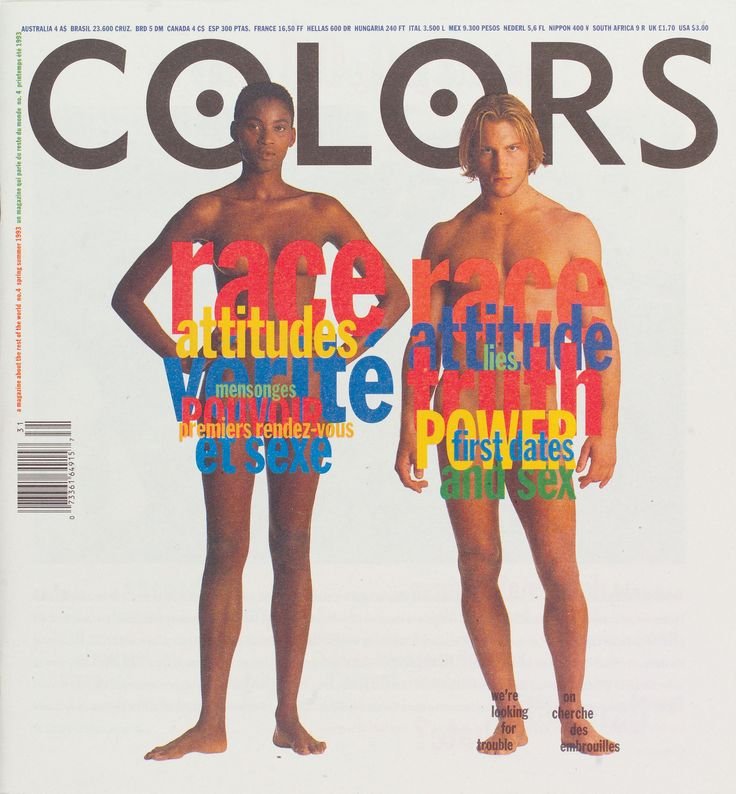

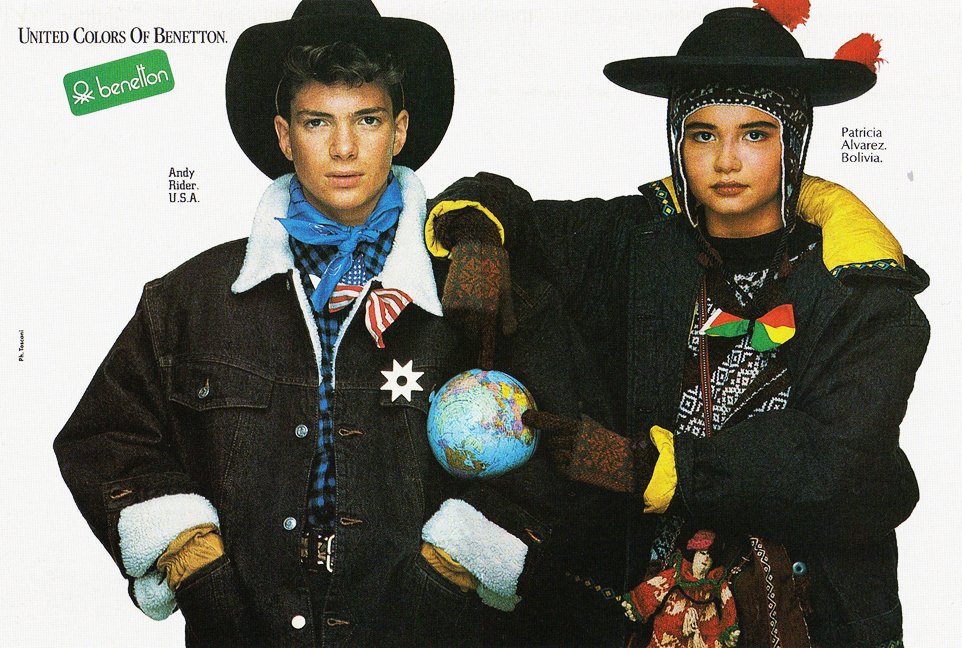

The infantilization of women in fashion was previously most evident in the conventions of fashion photography (as outlined by Erving Goffman’s longitudinal study on the consistent belittling of female models in adverts and editorials). Although the garments Goffman’s sample images may have had the adult feel of tailoring, lace and structure, it was how the models showcasing the garments were depicted that betrayed their demotion to ‘girls’ rather than ‘women.’ This has changed in the past few years. Now, the clothing itself has become more childlike, and invests in comfort & softness, ease of movement and playful designs (sometimes leveraging cringe millennial nostalgia to remarket 2000s-2010s intellectual property to its original audience, now armed with some disposable income and a desire to regress).

ModeSens (2024). Lounge Around Knit Henley Romper In Grey, Women’s At Urban Outfitters. [online] ModeSens. Available at: https://modesens.com/product/out-from-under-lounge-around-knit-henley-romper-in-grey-women-at-urban-outfitters-100320600/ [Accessed 26 Mar. 2025].

Even the naming conventions are toddler-coded. Consider the ‘Oatmeal’ jumpsuit, the ‘Lounge Around’ romper, the ‘bubblegum soft lounge’ set (a name that could easily refer to a child-friendly cafe specialising in milkshakes and sundaes). The designs are a curious mix of this naivety and the extreme body consciousness of a 2014 clubbing dress. They eschew the maximalist tendency of Lolita style, where toys become surreal accessories and childhood is mined as inspiration for unusual inspiration. They instead combine the competing aesthetics of bland, beige clothing with meticulous and heavy makeup, hair extensions and tanning routines. Whilst you could be forgiven for having flashbacks to Kanye’s inaugural Yeezy collection from 2015, this dissonance in effort between dress and appearance marks them as firmly differing styles (although a Kardashian influence looms large over both iterations).

PrettyLittleThing (2025). Cream Structured Contour Rib High Neck Jumpsuit. [online] PrettyLittleThing. Available at: https://www.prettylittlething.com/cream-structured-contour-rib-high-neck-jumpsuit.html [Accessed 26 Mar. 2025].

The tactile softness of this style of clothing has major appeal. Understandable, given the comfort of women has been viewed as anathema to stylishness for some time. In an absence of actual design, the softness and stretchiness of fabrics become the focus. Echoing the popularity of the ‘soft life trend’ (a rejection of hustle culture in favour of individual ease and happiness), babyfied clothing restores sensory enjoyment as the primary function of fashion. Revisiting materials, fabrics and feelings we relied on for comfort and safety as children invites us into a sensory nostalgia where our adult concerns can be soothed and sidelined. Whilst this can be positive, the obvious risk of this attitude is that it continues to deny the present realities that need facing. Perhaps the babyfication of fashion is merely a symptom of this wider cultural affliction.

References

Horton, C. B., Adam, H., & Galinsky, A. D. (2023). Evaluating the Evidence for Enclothed Cognition: Z-Curve and Meta-Analyses. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 51(2), 203-221. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672231182478 (Original work published 2025)