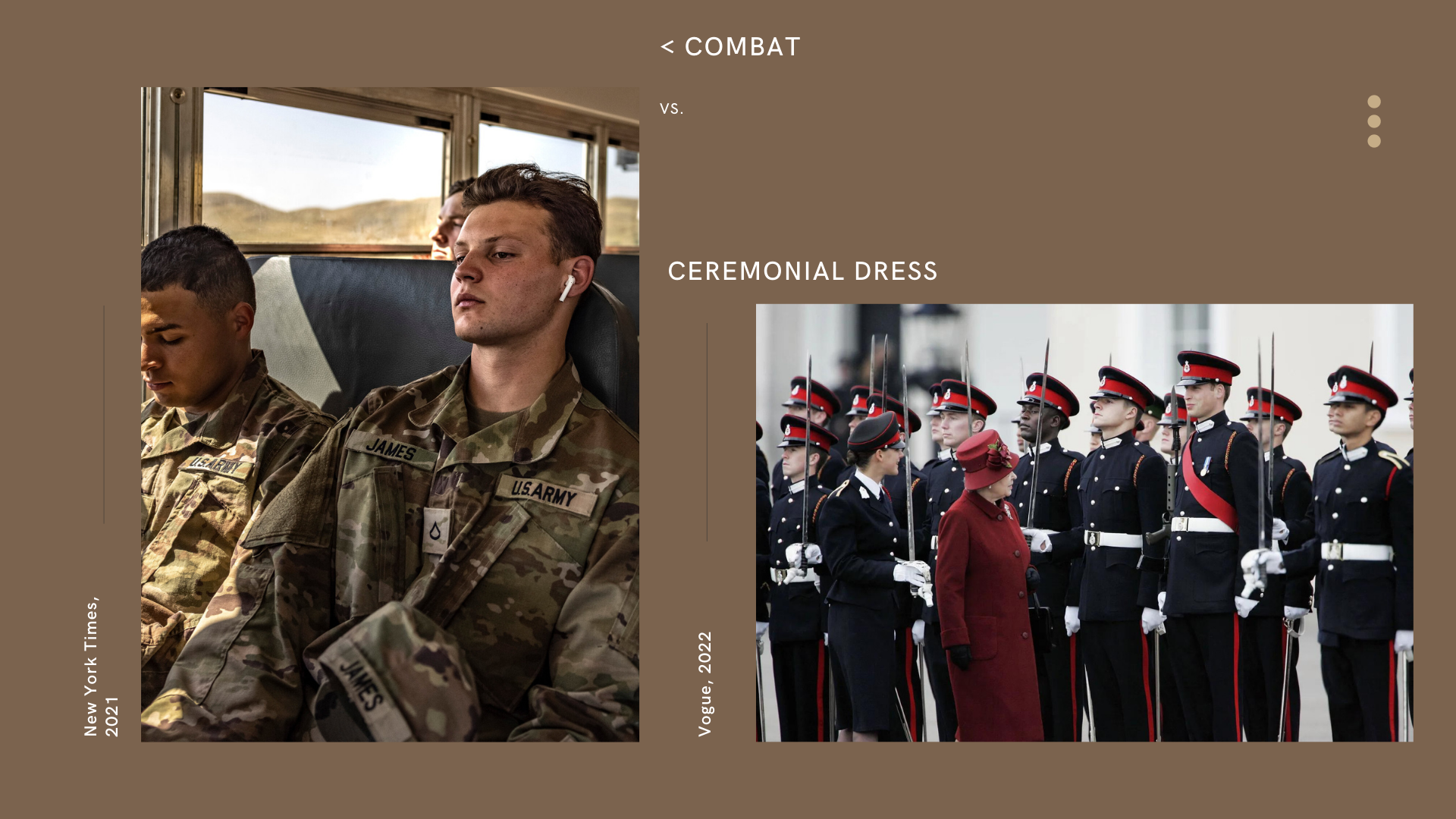

When it comes to military influences in fashion, we can identify two main trends. Firstly, there is the ornate version, referencing the ceremonial garb of various regiments and guards of honour. The second is more utilitarian in nature – drawing on the uniforms' silhouettes, colours and prints. Whilst the ceremonial strain of military-inspired fashions is powerful because it holds connotations of a certain status, sophistication and discipline, the utilitarian strain is much more ambiguous. ‘Combat dress’ is worn by those on the front line, not necessarily those in significant positions of authority, and is most commonly associated with ‘boots on the ground’ action. Camouflage, in particular, has become so ubiquitous in a fashion sector increasingly influenced by streetwear and the visual language of survivalism. This ongoing love story between the fashion industry, notoriously preoccupied with glamour, and this Plain (G.I Jane) print points to a desire to embrace and commercialize military motifs' functional and aesthetic value.

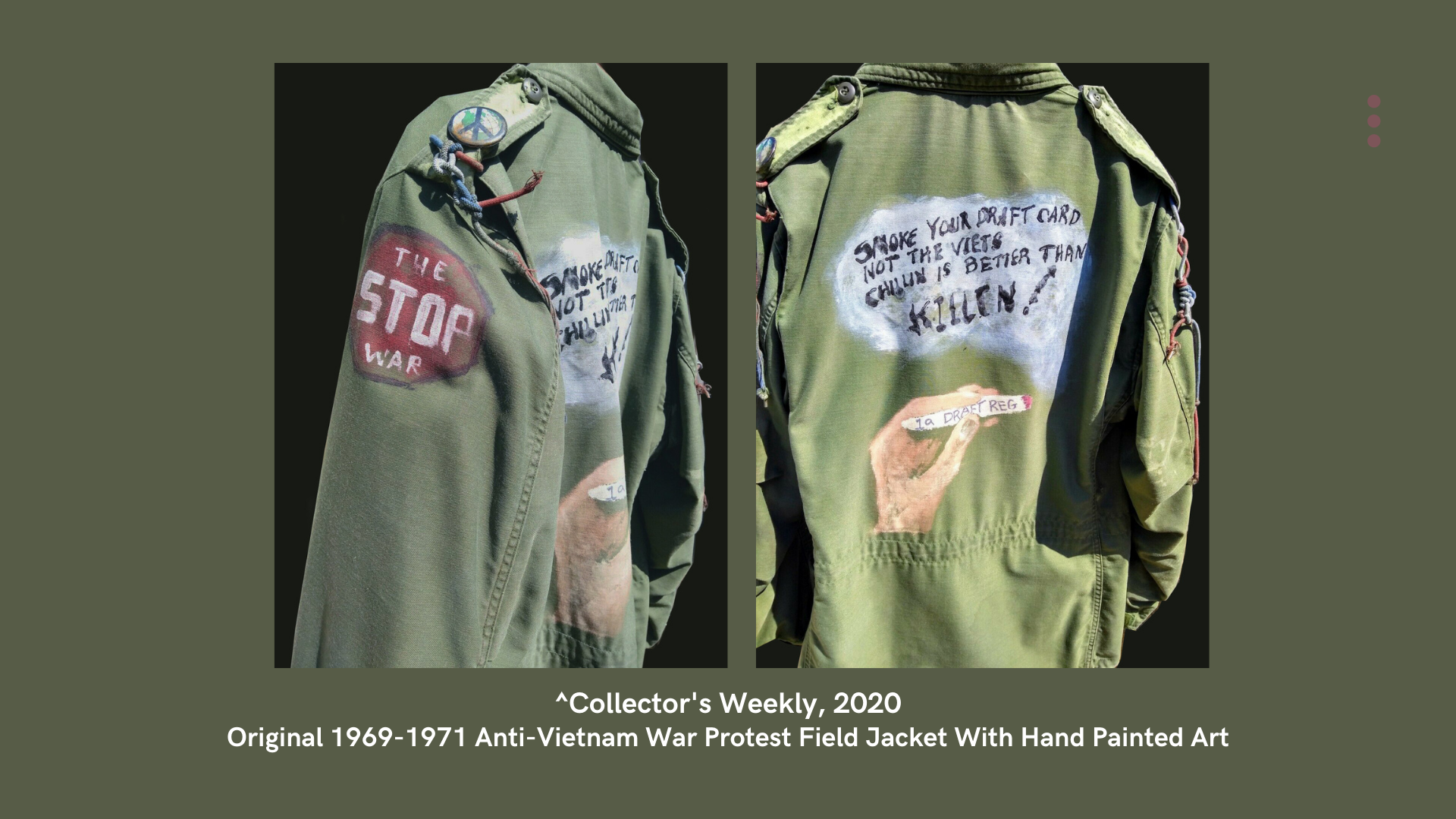

Camouflage and combat garments have undergone an interesting and uneasy evolution as they have been absorbed into fashion. They first entered the fashion mainstream when a surplus of military-issue garments was sold off to civilian populations after World War 2. These garments were bought up by lots of different people; among them survivalists, students, and activists. These last two groups, in particular, modified these garments as an act of resistance, absorbing them into the counterculture of the moment. Here, a standard issue field jacket has been painted with anti-war and pro-marijuana slogans.

Anti-war activists did this by writing on the jackets, patching them up and hacking at them in order to customise them. In this way, they were reappropriating the garments for their anti-war messaging and performing a sort of symbolic desecration. The influx of Vietnam veterans into the hippie movement, who sought comfort in its pacifist philosophy and sense of community, also accelerated this trend. Seeing veterans throwing their medals away and scribbling on their uniforms was even more powerful because they had previously served their country. In contemporary fashion, it would be easy to argue that camouflage has lost its countercultural status and become mainstream and, as a result, much less radical.

The use of camouflage in womenswear is particularly interesting. It has been argued that the uniformed soldier is one of the foundational representations of Western masculinity. Military studies academic Cynthia Enloe outlines that this has been the case since the second world war when nationalist propaganda firmly focused on the male soldiered body. Removing camouflage from its manly, military context is already starting to soften it for mass consumption. Scholar Paul Achter believes that in the military, the uniform aims to ‘collapse the distance between a service member and the garments’ - making one inextricably linked with the other. Fashion, on the other hand, does the opposite.

The fashion sector downplays, or even denies, the connotations of violence and even of political symbolism where militarized fashions are concerned because this excuses them from difficult conversations regarding the latter whilst enabling them to capitalize on commercial appeal unchecked. In 2015, cultural critic Troy Patterson commented on the absurdity of divorcing camouflage print from its original function by stating in the New York Times that ‘half of the people you see on the street are dressed to kill.’

Achter also reminds us that whilst uniforms have always served a primarily utilitarian purpose, there were dedicated historical efforts to create uniforms that ‘flattered [soldier’s] bodies’ and were part of a marketing effort to encourage young men to join the army. Therefore, we cannot say that trendiness and desirability have never been a part of the conversation surrounding military uniforms, even from within the establishment. Indeed, he sees a clear fetishization of military aesthetics in contemporary popular conscience, accelerated by the culture industries championing ‘new militarism’. This 'new militarism' frames military technology, dress, occupations and endeavours as desirable, exciting and heroic.

Some designers have played with camouflage print in exaggerated forms, almost parodying it. Stephen Sprouse took Andy Warhol’s experiments in large-scale Pantone-coloured camouflage prints into the fashion world, creating something so vibrant it verged on the ridiculous. In this example, it is the technicolour palette subverts our expectations. This suit is currently a part of the Met Museum’s permanent fashion collection, a testament to its significance.

Other designers were less exuberant. Versace's Spring 2016 range had some of the thick graphic prints and neon accents of Stephen Sprouse but took a more subtle and sophisticated approach to the print. Donatella played with the proximity of camouflage print to leopard spots, suggesting both could be as sexy as each other, particularly in micro-mini skirts and low-rise trousers with plenty of skin on show. Practical generously-pocketed jackets and backpacks accessorized the looks. Here, military-inspired fashion is presented as alluring and feminized. The camouflage is reimagined as adjacent to animal prints, which have connotations of primal instincts & femme fatales.

Some designers have started with the available deadstock materials and constructed a fashion narrative from the fabric itself. Marine Serre’s 2022 collection featured a range of garments entitled ‘desert damask’ that combined different disruptive pattern materials together into a patchwork. The softer, sandy palette also tempers the camouflage print, making it feel more delicate and less threatening. These looks were presented on the runway alongside other upcycled outfits constructed from quilted duvets, recycled hoodies and repurposed tartans. Critics noted that these looks felt more protective than apocalyptic, with the olive branch necklaces used as a hopeful-if-clumsy metaphor for peace.

Generally speaking, high-fashion Camouflage print is often sold as a utilitarian interpretation of feminine luxury. For example, Jean Paul Gaultier's couture looks are dramatic without being finicky. However, many fashion scholars suggest that there is no more crucial time to interrogate the destigmatization and glamourization of military dress elements in the fashion media than when we are engaged in a seemingly endless and increasingly difficult-to-define state of war. The conflict in Ukraine, the questions of proxy wars, and the unclear conclusion to the Global War on Terror should certainly prompt some discussion about what is celebrated on catwalks and sold in stores.

Achter characterizes the representations of militarized fashion as being largely free from ‘patriotism... dirt... and trauma’, placing these designs in a neutralized aesthetic that insists on coolness and urbanity. He sees this positioning as largely responsible for emptying traditional military styles and prints, such as camouflage of its radical political potential.

Due to its deeply gendered origins, camouflage positions itself as liberating women from more tedious or old-fashioned forms of luxury. It offers itself up as a cooler, more contemporary option. One could argue that this is even more noticeable in the luxury sector, where brands generally favour decadent, ill-considered and uncomfortable design choices to accentuate exclusivity. Therefore, high-end brands using military aesthetics benefit from its rich symbolism and a product that can be marketed to women as fashion with functional value.

After all, isn’t suffering for fashion at best outdated and at worst oppressive?

In this way, it also sells itself as empowering. The popular cultural associations of camouflage are still dominated by militarized masculinity. Its translation into womenswear suggests that in wearing it, we can take on the qualities of the male military hero; strong, capable and assertive.

Two main requirements guided the design evolution of military clothing. Firstly, the need to be able to produce garments on a massive scale, and secondly - to do this for relatively low prices. This prioritized both ease of use and efficiency. In contemporary womenswear, this utilitarian sales pitch may be another reason camouflage and military-inspired clothing has become so ubiquitous – it can be praised for being genuinely easy to wear. Other garments in this vein tend to be relaxed, informal, and often unprofessional - for example, consider the recent trend towards athleisure…

But military-inspired fashion never feels sloppy because of its longstanding cultural associations with discipline and rigour. You get a double whammy as a designer. You can play on the forbidden strictness and sexiness of the uniform arising from its military origins and exploit the accessibility and practicality of the silhouettes and fabrics used. Subverting these styles by adapting them for the female market can be easily and convincingly packaged as a form of fashioned empowerment, offering us style without sacrifice.

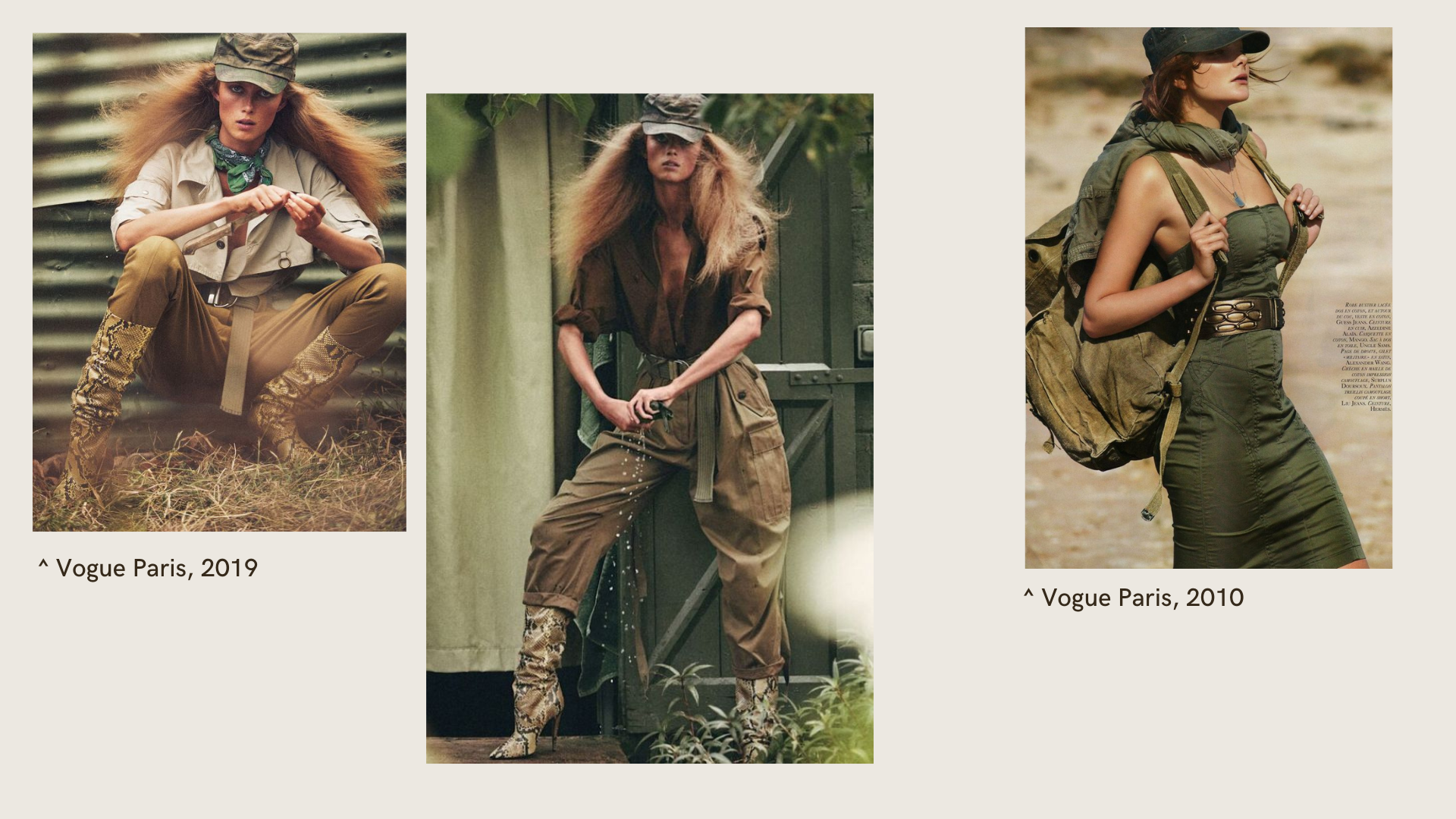

In a similar vein, the imagery associated with military-inspired trends across the fashion press often plays on associations between adventure, self-sufficiency, utility, and exotic travel. This positions you, the consumer, as an explorer, not a soldier.

This reinforces the phenomenon described by Achter as military-chic, where military-inspired fashion is detached from its original use-purpose and aligned with new, more palatable symbolic associations. This takes place across popular culture - from music videos to fashion magazines to films. This all reassures consumers that military-inspired fashion, as one cultural commentator puts it, is ‘just another choice among many others.’

Furthermore, military dress in fashion treads a fine moral line and a legal one. This raises questions about what is considered ‘stolen valour.’

It is one thing to ask ourselves what is appropriate in fashion and another to ask ourselves what is acceptable. In the UK, the uniforms act of 1984 imposed legal restrictions on military dress. The act states that ‘It shall not be lawful for any person not serving in Her Majesty’s Military Forces to wear without Her Majesty’s permission the uniform of any of those forces, or any dress having the appearance or bearing any of the regimental or other distinctive marks of any such uniform’ It makes an allowance for the public performance of stage plays, musical performances or... circus acts.

The draw of the military uniform and the high public trust, respect, and reverence it can inspire has seen a phenomenon of military imposters showing up at events with medals that have been purchased, not earned. The internet has made all forms of militaria easier to identify, falsify and purchase, so perhaps it is inevitable that some would see an opportunity to use these garments as a costume.

Where fashion ends and impersonation begins is an interesting question – it would appear that making use of decorative medals or honours crosses a line. Academic Amanda Laugesen chronicled a controversy in which Kate Sylvester, an Australian designer, was forced to issue a public apology for the use of military medals in her 2008 catwalk show. The show was titled ‘Royally Screwed’ and was intended to be an ‘anarchic take on the monarchy.’ Laugesen points out that although fashion designers should be allowed to explore political themes and motifs in their work, a more thorough understanding and contextualization of ‘military emblems and symbols’ would be helpful if we are really to expand our perspectives on the way ‘in which contemporary society understands the memory of war and the meaning of military service.'

And sometimes, the clothing of war as it is staged in fashion images pushes the bounds of acceptability. Critic Elizabeth Wilson commented on this Steven Meisel for Vogue Italia shoot, stating, ' Khaki, war, sex, and glamour come together... half-clad models pose like prostitutes for tattooed squaddies in an Iraq army camp.’ The shoot is provocative, pairing models in revealing high fashion with soldiers in gulf-war standard issue garb. Notably, the soldiers are often removing or only in partial uniform, a motif that recurs in war films when soldiers experience some sort of mental breakdown or psychotic episode.

The removal of the uniform is often representative of an identity crisis, of turmoil, of no longer being able to adhere to the rules of the military environment. The rejection of the proper dress code is, by design, also a rejection of authority. Here, the way the camouflage is only partially committed to, as well as the models' suggestive gendered positioning, makes the images so contentious.

The endurance of military trends in the field of fashion is a testament to its versatility, as well as our continuing fascination with its associations of power, violence and discipline. The way different designers use camouflage varies; some opt for a quite literal interpretation and create doomsday-prepper-style outfits. Marine Serre's make, do and mend production approach made military fabrics an obvious choice of materials. Blumarine's return to the early 2000s is emptied of any obvious political intent, and Celine presents us with something typically straightforward; sending a camouflage parka jacket down the runway with its harness still attached. These are just a few examples among many.

Fashion must tread a fine line when it comes to the incorporation of military motifs, including camouflage print. Its marketability relies on its reinterpretation, not stoking the ire of critics, commentators, the military establishment, and now the wider internet. Military-inspired fashions must continue redeployed in designs and contexts that diverge considerably from their original use. By doing so, it minimises the risk of crossing any legal line. And more importantly, it can maintain that distance from the realities of war that are anything but enticing.

The institutional interpretation of military dress tends towards conservative and de-individualized appearances, whereas fashion ‘is defined by provocation and the search for novelty’. Secondly, where the army relies on a literal and concrete interpretation of uniformed dress, fashion exploits its metaphorical potential and plays with those ambiguities. Finally, the military as an institution must uphold the gravitas and integrity of the uniformed body, whereas fashion as an industry has the license to play with a ‘campy, fun, ironic tone’ in its appropriation of the styles. One thing is certain... when fashion and the military come together, there'll always be some sort of symbolic conflict.

References

Achter, P. (2018). ‘Military Chic’ and the Rhetorical Production of the Uniformed Body. Western Journal of Communication, 83(3), pp.265–285.

Cohn, C. and Enloe, C. (2003). A Conversation with Cynthia Enloe: Feminists Look at Masculinity and the Men Who Wage War. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(4).

Le Masurier, M. (2019). Like Water & Oil? Fashion photography as journalistic comment. Journalism, p.146488491986092.

Patterson, T. (2015). How the Army Jacket Became a Staple of Civilian Garb. The New York Times. [online] 5 Mar. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/08/magazine/how-the-army-jacket-became-a-staple-of-civilian-garb.html [Accessed 25 Mar. 2023].

Rall, D.N. (2014). Fashion & war in popular culture. Bristol, UK; Chicago, Il: Intellect.