How would you describe Claires Accessories to a martian? You’d probably say it’s a little purple shop – usually no more than a small open cubicle of shopping centre real estate – that uses every available surface to display its trinketry. In one corner, they have a high chair reserved for piercing earlobes which is a sort of middle-England rite of passage. They then upsell you saline water as aftercare for an extortionate profit margin, informing your already reluctant mother that you may develop sepsis if you do not religiously daub at your new sparkly implants twice a day for the next four weeks.

The products in Claire’s are, as the name may suggest, accessories. They cover hair, jewellery, some makeup, piercings, gloves (usually fingerless), and hen-do paraphernalia. You’d be hard-pressed to purchase a whole outfit from her - unless you were willing to get very creative with some legwarmers and a set of My Chemical Romance limited edition badges. Everything is made cheaply, in hard-wearing metal alloys and slick plastics, built not necessarily to last but also never to disintegrate.

Claires Accessories Shop, Southampton

Going to Claire’s and purchasing your chosen accessories is where you decided Who You Were Going To Be. It offered up a selection of identities and then gave you a 3 for 2 deal on them. Gothic? Boho? Girly-girl? Emo? A person who got lost on their way back from a warehouse rave and ended up in Swindon retail centre?

It never felt like it was too much to contend with, unlike the TikTok aesthetics of today, because each earring, wristband or flower crown was carefully positioned alongside its accompanying styles. In this way, you navigated the grids of plastic panels that displayed Claire’s wares and did so systematically and with great consideration. Even if its blatant commercialism now incites a bit of guilt, at the time it was exciting and fun. Constructing yourself through this sort of disposable consumer culture was enjoyable. Nowadays, tween identity formation is generally presented in popular culture as a site of great anxiety and anguish.

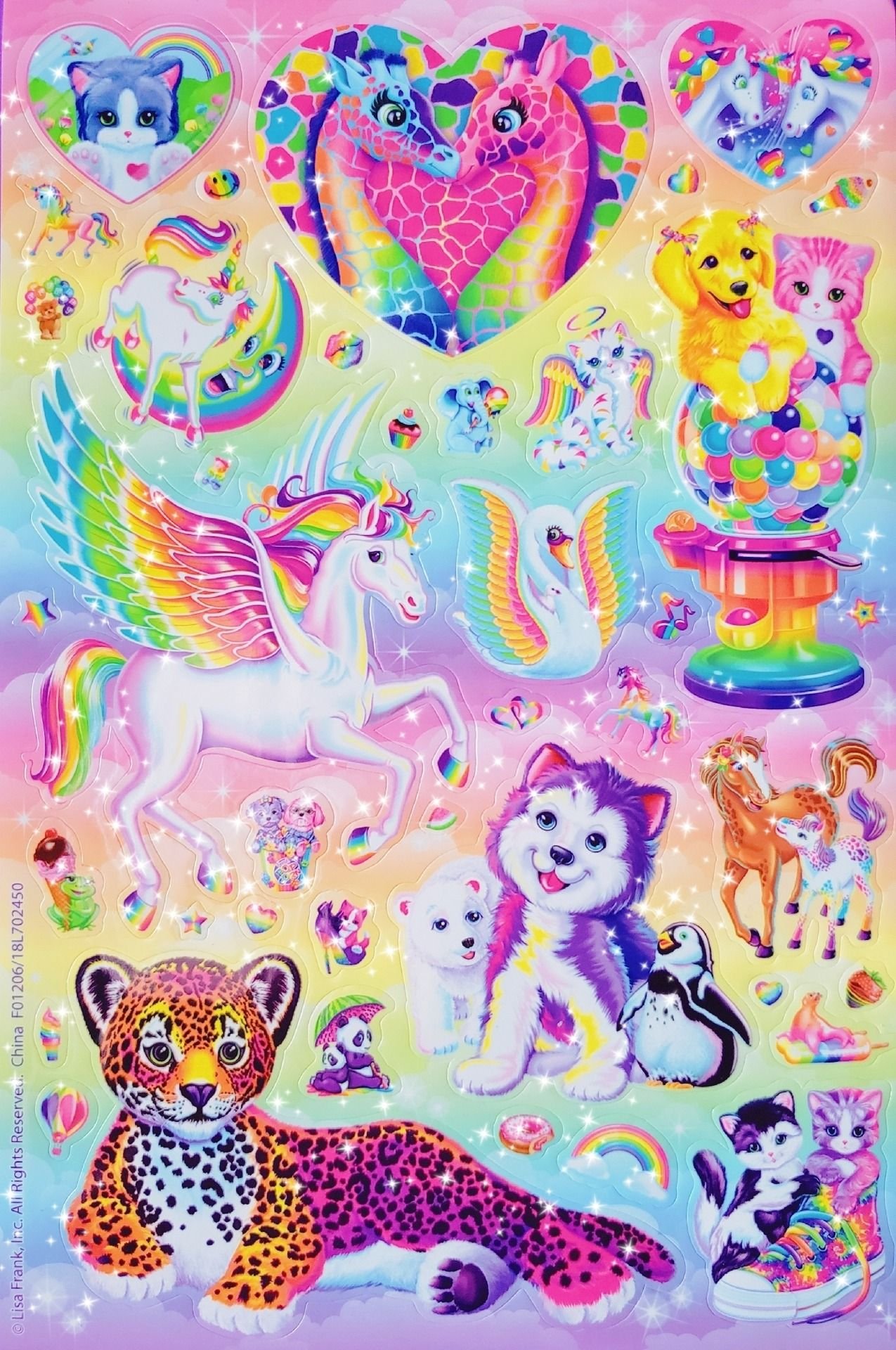

The power of Claires and its cartoonish cuddly toys, sparkly necklaces and fluff-topped gel pens was that it sold itself as a place where identities could be tried on, tested out, and modified for bargain prices. One week you might want to opt for a mesh tattoo sleeve and see how good it felt to be a badass. The next you would decide to buy a pencil case for the new school year that you placed an almost unbearably high expectation of academic transformation on. The barrier to participation was low, and the commitments were half-hearted. As they should be at such a formative phase.

Lisa Frank sticker page

Claire’s official brand values are listed on its website as ‘passion’ ‘self-expression’ and ‘continual movement forward’ but the company has faced recent financial strain. The death of the high street and teenagers instead flocking to Depop instead to buy drop-shipped AliExpress butterfly hairclips from who they perceive to be ‘independent sellers,’ has proved a challenge.

The considered and organised merchandising of Claires Accessories no longer appeals – seen as patronising or infantilising – as opposed to a gentler way of easing young girls into the realities of contemporary image construction and selfhood. Tweens want to treasure-hunt for themselves now, they don’t need an international corporation (boo, hiss!) doing it for them.

I like to think of Claire herself as an agglomeration of everything that is good about being a woman. She has big, bouncy hair, never experiences indigestion and her glittery acrylics are always intact. She’s a sort of north star, guiding girls through how to rebel just enough to not compromise any pocket money or actually reduce your mother to tears (a cartilage piercing here, wash-out neon green hair spray there.)

Claire - the allegory - has been slain by market forces beyond our control. Don’t send flowers. Unless they’re artfully arranged on a plastic headband as a crown. The tween - the reality - has been absorbed into the teenager - she’s busy getting her eyelash extensions filled in and recording herself on Snapchat.

It seems that the age-appropriateness of the plush purple pencil cases, rainbow-tufted unicorns and puckered neon plastic rubber friendship bands no longer appeal to an Instagram audience who want to skip straight to crop tops and designer sneakers. That’s fine, but it does feel premature to be committing to a vision of adulthood at one of the only times in life other people won’t be constantly pressing you to dedicate yourself to a specific pathway (career), identity (sexuality) and lifestyle (marital status).

Losing Claires will represent a loss for girlhood, which is no longer being allowed to exist as an intermediary period between being a child and entering the adult world, in which your identity and the way you present yourself can be as elastic as the straps on your (Made In Taiwan) iridescent fairy wings.